“Abandon hope all ye who enter here,” reads a sign above a doorway.

Staffers are getting ready for an afternoon staff meeting to discuss the hurricanes and tropical storms already on the move across the Atlantic, James J. Callahan III, Nassau’s Office of Emergency Management (OEM) commissioner, tells the Press.

At 42, there’s a touch of gray in his hair but not much evidence that the stress of the job has taken its toll. He radiates efficiency and good humor. Callahan, who’s also the deputy mayor of Malverne as well as its fire commissioner, has been in charge of this facility for four years, and now he’s preparing to relocate the office to its brand new headquarters in Bethpage. He expects to be there in a month, and retain this facility as a “hot backup,” ready just in case. The new location is larger, and promises more regional cooperation with other agencies that can share the space with them when necessary.

On the door to his office, OEM magnets spell out S.O.S. Lying atop a nearby filing cabinet is an orange and red Vulcan-model Nerf gun.

“When you deal with the end of the world all the time—because that’s what we plan for—you have to have fun in this business or otherwise you would go insane,” he says.

After a discussion on flood zones, evacuation routes, shelter preparation, food and water distribution, as well as manpower allocation, one comes away with the sense that this man—a father of four who also has a law degree as well as extensive training in handling emergencies—is the guy you want making the tough calls when the weather gets rough.

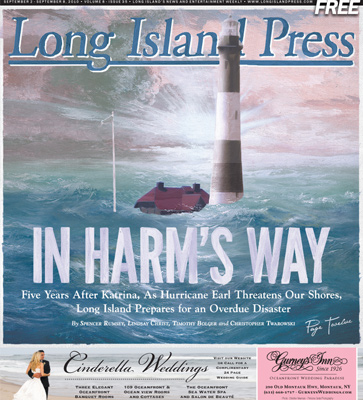

A house floats in Westhampton Bay, Feb. 25, 1993, a victim of last December's nor'easter storm. The storm created an inlet, upper left, named Pike's Inlet, which is widening daily. It destroyed many homes and beach areas prompting a Long Island Coastal Conference to be held in June, in an attempt to save areas in danger of being washed out to sea. (AP Photo/Mike Albans)

He says Katrina has taught his staff a lot, and one lesson is, you have to take care of first responders’ families, otherwise they’ll get increasingly distracted and lose their focus as they work nonstop for days on end. So Nassau OEM has helped set up special shelters to accommodate about a thousand family members in the event of an evacuation.

Regular shifts during “an event,” as they call catastrophic weather, last about 16 hours. During the downtime, staff and responders can check on their families and get reinvigorated for the daunting tasks ahead.

Looking at the history of hurricanes on Long Island, Callahan says grimly, “We’re overdue.”

His people monitor approaching storms days in advance. He explains the time table they use for moving people out of danger: For people in hospitals and those with special needs, evacuation is voluntary 48 hours before the storm’s landfall, and mandatory at 36 hours. For the general public, evacuation is voluntary at 36 hours, and mandatory at 24 hours. And those who ignore the order can be charged with a Class B misdemeanor and face up to a year in jail.

“I’m not going to arrest you,” he says. “We don’t have the manpower.”

But obeying the order to evacuate is a smart idea, he stresses, and he has the topographical maps, prepared by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, to prove it. Nassau’s South Shore is divided into four zones, as determined by how far inland a storm surge could go.

A Category 3 hurricane, with sustained winds more than 120 miles an hour, would bring a surge more than 20 feet high. For Long Beach Hospital, for example, this means the second floor would be underwater. So, Zone 1 is Long Beach, Zone 2 is Bellevue and Baldwin Harbor, Zone 3 goes up to Sunrise Highway, and Zone 4 extends to the Southern State.

Callahan stresses the need for residents to be aware of where the county’s emergency shelters are, should they be activated, but also stresses the need for residents to make plans in advance of potential disaster—now. The county has 25 shelters that have been pre-equipped with supplies.

Because the reality is, there’s only enough room for about 60,000 people in the general population shelters for both Nassau and Suffolk counties, with about 240,000 people living below Sunrise Highway.

Callahan’s office has set up four evacuation routes: Route 878 to Peninsula Boulevard, Long Beach Bridge to Grand Avenue, the Meadowbrook Parkway and the Seaford-Oyster Bay Expressway. All told, moving people out of those four zones could take about 27 hours, 17 if things go smoothly. And you know on Long Island, that’s a long shot, at best.

“We are prepared,” says Craig Craft, Callahan’s acting commissioner. But, he stresses, residents “will have to take an active part in their own survival!”

Long Island is no stranger to vicious storms, though it may be not at the top of most residents’ minds. Yet it was a hurricane that in fact actually shaped our geography.

Grotto in Saltaire, Fire Island, marking the original site of Our Lady Star of the Sea Church, swept away by the 1938 storm.

Wrath of God

The Long Island Express hit on Sept. 21, 1938, unexpectedly and ferocious. The hurricane was projected to curve out to sea, but at the last minute an area of high pressure kept the storm close to the coast and moving northward. It slammed Long Island a mere six hours after it had passed North Carolina—moving at 70 mph—the fastest known forward speed for a hurricane ever recorded. Since the forward speed of a storm adds to the intensity of the wind, Eastern Long Island saw winds that exceeded 180 mph, according to historical accounts.

Compounding the devastation was the fact it hit at 3:30 p.m., a few hours before astronomical high tide, which was even higher than usual because of the Autumnal Equinox and a new moon. This produced waves between 30 and 50 feet and storm tides of 14-to-18 feet in places such as the Hamptons. The community hit hardest was Westhampton, with at least 150 houses destroyed and a storm surge that caused more than 6 feet of water to flood Main Street a mile inland. More than 50 Long Islanders were killed. The total cost of the storm for Long Island was around $6.2 million, in 1938 prices. Experts put the price tag for damage of a similarly strong storm at about $1 trillion. Twelve new inlets were also created by the storm, including the Shinnecock Inlet.