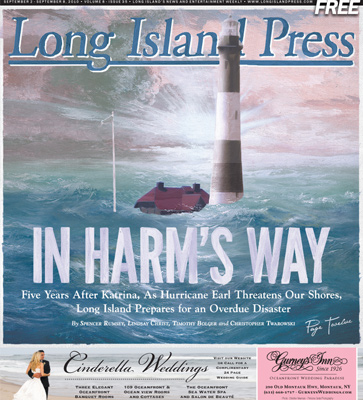

Waves of Mutilation: Some of the devastation across Long Island left in the wake of the Long Island Express Hurricane of 1938 (photos courtesy of Nick F. Panico III)

About 115 years prior, a storm christened the 1821 Norfolk and Long Island Hurricane hit New York City directly on Sept. 3. The storm, which researchers estimate was between a Category 3 and 4, caused a 13-foot storm surge. The East River and the Hudson River met across Canal Street, and buildings throughout Manhattan were destroyed or suffered wind damage.

In one storm shortly before the turn of the last century, an entire island was not as lucky to come back from the brink. A Category 2 storm in 1893, one of the last to land a direct hit on New York City, washed away a mile-long resort island off the shore of Far Rockaway known as Hog Island—a local Atlantis of sorts.

“We’re used to structures on islands disappearing, but were not used to islands themselves disappearing,” says Nicolas K. Coch, professor of geology at CUNY Queens College.

Coch discovered the fate of the doomed island when a dredging project unearthed bar room relics of Hog Island from the ocean floor and dumped them on a newly replenished beach in 1995.

Then there was Hurricane Gloria, the last hurricane to make landfall on Long Island, in 1985. Gloria caused a considerable amount of damage and left many people without power for more than a week. Yet as bad as Gloria’s damage was, there’s a misperception among many about the storm, explains Manorville resident Nick F. Panico III, a recently unemployed science teacher and fervent weather enthusiast whose curriculum had included a heavy portion of instruction about hurricanes.

“A lot of people view that as a major hurricane,” Panico explains. “It was only a Category 1.”

Panico has experienced four hurricanes firsthand, some by circumstance, others by choice, the latter including Katrina. He was 8 years old when Gloria hit, and remembers having to evacuate his Mastic Beach home. He also vividly remembers being without power for 10 days.

Panico has experienced four hurricanes firsthand, some by circumstance, others by choice, the latter including Katrina. He was 8 years old when Gloria hit, and remembers having to evacuate his Mastic Beach home. He also vividly remembers being without power for 10 days.

In 1991, Hurricane Bob brushed the eastern tip of Long Island. Even though Bob did not make landfall, the National Hurricane Center recognizes it as a Category 1 hurricane for Eastern Suffolk, as the area did have hurricane conditions. Panico was also forced to evacuate his home for this storm, too.

In 2005, Panico’s passion for hurricanes got the best of him, and he drove from Florida, where he had been vacationing, to greet Katrina. He arrived in northern Mississippi early Sunday morning, and found a local school to ride the storm out. The devastation he saw was colossal.

Many of those images, as well as photos from previous storms—including a collection of newspaper covers and photographs from the aftermath of the Long Island Express—adorn the website of another hurricane enthusiast, Scott Mandia, a professor of physical sciences at Suffolk County Community College.

The worst-case scenario for Long Island would be a fast-moving northward moving hurricane of Category 3 or 4 strength striking at astronomical high tide, much like the one in 1938, he warns.

The worst-case scenario for Long Island would be a fast-moving northward moving hurricane of Category 3 or 4 strength striking at astronomical high tide, much like the one in 1938, he warns.

“The worst result will not be day one but will be the weeks or months afterward, where roadways may be blocked by felled trees and other debris and widespread prolonged power outages,” he says, echoing the words of Williams and Levy that it would be such a storm’s aftermath where the real difficulties would begin.

According to Mandia, who has conducted extensive research into the “what ifs” of a Long Island hurricane, the probabilities of LI and the New York Metro region being slammed with ferocious storms in 2010 are two times greater than in previous years. For starters, his data indicates there is a 6 percent chance New York City and Long Island will be hit with a hurricane this season, double the normal value. Also doubled is the probability New York City and Long Island will be hit with a Category 3 or higher hurricane.

“We can expect a hurricane for Long Island and New England every 9 to 10 years, so we’re overdue just for a hurricane, and we’re also overdue now for a major hurricane,” adds Panico.

According to the National Weather Service, roughly every 70 years, Nassau and Suffolk counties should be hit by a Category 3 storm.

According to the National Weather Service, roughly every 70 years, Nassau and Suffolk counties should be hit by a Category 3 storm.

The physics of the New York City/Long Island area also make it more vulnerable, adding to the impossibility of a total evacuation. Bridges in the region, such as the Verrazano and George Washington, would have to be shut down early because they are up so high that these structures would experience hurricane force winds first, according to a 1990 study by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

If a major hurricane were to hit, a computerized storm surge prediction model developed by FEMA and the National Weather Service called SLOSH (Sea, Lake, and Overland Surge from Hurricanes) foretells that John F. Kennedy International Airport would be under 20 feet of water and sea water would pour through the Holland and Brooklyn-Battery tunnels and into the city’s subways throughout lower Manhattan.

Based on the most recent storm surge maps for Nassau and Suffolk counties, as well as Mandia’s research, a Category 1 hurricane would cause both shores of the North and South Forks to be inundated with water. Montauk Point would be completely cut off from the rest of the South Fork. During a Category 3 hurricane, Montauk Highway would be covered by water, as would most of the two forks. Residents living south of Sunrise Highway would be forced to evacuate their homes.

A Category 4 hurricane, says Mandia, could produce storm surges as high as 29 feet in Amityville Harbor and 24 to 28 feet in Atlantic Beach and Long Beach, South Oyster Bay, Middle Bay and East Bay areas.