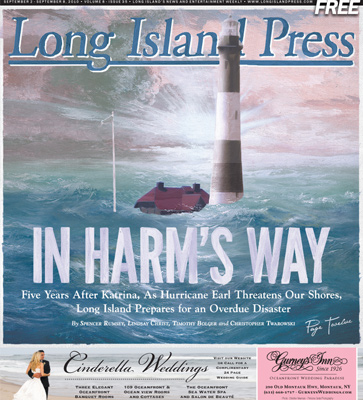

Harsh Reality

Whether the next hurricane to hit LI zigs or zags east or west upon landfall, precisely where the storm rolls ashore makes little difference, since erosion will likely be seen across all ocean beaches. Which seaside communities will suffer storm surges that wash waves over the dunes and sweep homes away is the million-dollar question.

Countless houses caught in path of past big storms now call the bottom of the Great South Bay or Atlantic Ocean home. More than 1,000 LI residences were said to be destroyed in the ’38 storm, including more than 500 on Fire Island, 29 in Oak Beach and the rest in the Hamptons and Montauk. The “Ash Wednesday” nor’easter of ’62 washed away 170 South Shore homes. A series of nor’easters in late ’92 and early ’93 destroyed 66 homes on Fire Island as well as 190 of 240 homes on the western tip of Westhampton Island that later became known as the Village of Westhampton Dunes.

Those figures don’t include the houses that were lost a handful at a time during intermittent storms. But anyone who can afford a home with an ocean view knows the price is a possible evacuation order when the inevitable Big One sets its sights on LI.

“Every year they say this is it,” says Gary Vegliante, longtime mayor of Westhampton Dunes, a village that has rebuilt itself to nearly 300 homes after almost being wiped off the map for the second time—the area lay claim to the highest number of lives and houses lost in ’38, too. “There’s only so much preparation you can do, then you gotta buckle down.”

Risky living or not, barrier beach dwellers are cognizant of the threat they face and understand their contingency plans are even more strict as a result.

“It isn’t like the old days where we had to go out and knock on everyone’s doors,” says Gil Hanse, an emergency preparedness coordinator for Town of Babylon, where the hamlets of Oak Beach and Gilgo on the eastern tip of Jones Beach Island would be at risk. For such remote regions, reverse 911 comes in handy—the aforementioned ability for police and emergency responders to send out mass notifications to entire towns and villages at once.

If push comes to shove in the City of Long Beach, fire and police crews will also conduct old-fashioned roving loudspeaker announcements if there is a call to evacuate.

“There’s no Red Cross in the city, so you really have to get out,” says Mary Giambalvo, spokeswoman for the city, noting that complacency can be an issue since it has been more than two decades since an evacuation there.

For all the logistical headaches involved in protecting people to these eastern and western barrier islands, it is the one at LI’s midpoint backed by the Great South Bay—by far the South Shore’s largest bay—Fire Island, that poses the greatest challenge.

Fire Island requires local firefighters go door-to-door to ensure no one is left behind to fend for themselves. Since there are no cars allowed, except for the few residents with four-wheel drive permits, almost everyone gets off the same way they got on: via ferry.

It is a time consuming, tedious task. Local cops and firefighters don’t leave until they are sure everyone is out.

“You don’t want to be stuck on Fire Island without any help,” says Ian Levine, spokesman for the Ocean Beach Fire Department, the island’s largest firefighter and EMS service. “We’re very narrow, we’re only two blocks wide at most parts,” Levine adds, suggesting the strong possibility of a breach in the island the next time a big storm comes to town.

While the issues facing the South Shore barrier islands appear perilous, few have it as bad as Montauk, the easternmost tip of the South Fork that juts out into the ocean and gets caught in nearly every storm that passes by as a result.

“It’s very hard to evacuate an area like this if you had to get out,” says Suffolk County Legis. Jay Schneiderman (I-Montauk), who runs Breakers Motel in the hamlet that colloquially refers to itself as “The End.”

With traffic that bottlenecks on Route 27 even when the weather is perfect, ordering everyone to leave Montauk at the same time would prove daunting, which is why storm plans typically call for residents to head to higher ground or a shelter. Should a storm knock out power, water would be cut off as well, because many homes in the area operate on private wells and are not hooked up to the public water system.

But Montauk has seen worse. After all, it briefly was an island in ’38 after the ocean breached Napeague Harbor.

Regardless if Earl, Fiona or any hurricane strikes our shores, Long Island’s emergency management personnel, such as Suffolk’s OEM Commissioner Williams, will be planning, strategizing, preparing.

“We’ve been holding drills and holding drills and holding drills, and no one wants the hurricane to come, and I’ll be the first to admit—there’s going to be some bumps in the road, because there always are—but, that’s the reason why we do these drills,” he says. “I hope it doesn’t come. But we’re kicking everything into place. And if this one doesn’t come or the one comes next week, we’re even more ready for that one.”