Panico points out another chilling thought: As prepared as emergency officials are, and as many improvements there have been in recent years (such as more precise flood maps, etc.), no one’s 100 percent sure how effective they truly are.

“The emergency planning has gotten their act together in the past five or 10 years—but it’s never been tested,” Panico says, soberly.

He fears the true height of a storm surge would be greater than predicted and that some shelters themselves may be at risk. He also worries additionally about the sustainability of North Shore power plants.

Nassau’s Callahan tells the Press water treatment facilities—such as the troubled Cedar Creek sewage plant in Wantagh—would also be at risk.

Some believe high winds won’t do too much damage to Long Island’s housing stock because houses here are built to withstand snow loads and hence are heavier than structures in Florida. Callahan insists, however, that until the state adopted a more stringent building code in 2003, houses didn’t have to withstand more than a 74 mph wind, noting that Gloria was only a Category 1 storm when it made land with 85 mph sustained winds. A Category 3 could blow roofs off from the inside.

Long before the winds reach gale force, the Long Island Rail Road will shut down to preserve equipment. Crossing gates will be removed, and power turned off. The Far Rockaway and Long Beach lines will be closed.

“You’re not going to have a track or signal gang out in the middle of gale force-plus winds that are potentially hurricane strength,” says Mike Charles, an LIRR spokesman. “So you have to batten down the hatches, so to speak, several days ahead of time.”

The Red Cross has about 1,800 volunteers trained for this emergency. They would oversee the shelters.

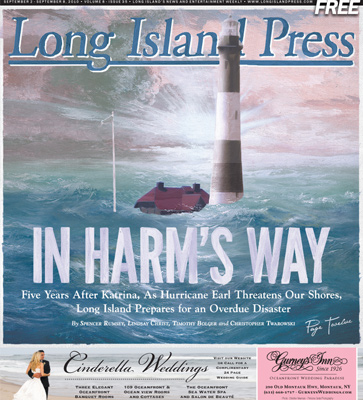

New York State Office of Emergency Management's tidal surge map for Long Island.

“It’s just a matter of getting our volunteers there, popping the locks and opening for business,” says Sam Kille, a spokesman for the Nassau chapter of the American Red Cross.

“When winds hit 55 miles per hour, law enforcement is going to be pulled off the roads, and bridges are going to be closed,” says Kille, “so the time to take action is while the sun is still shining before the rains and the winds kick in. We worry about people not listening and waiting until the last minute.”

About 24 hours before the storm would make landfall, 500 National Guard troops would go on active duty. There are also about 700 cadets from the Merchant Marine Academy ready to assist. The New York State Department of Transportation has about 400 maintenance crew members on hand for its 5,300 miles of roadways, with another 500 personnel to assist in the effort.

National Grid, in conjunction with LIPA, will draw upon its crews throughout New England to aid in restoring power. But they know from past storms that the process could take weeks. Their prediction is that a Category 3 storm could leave some Long Islanders in the dark for 30 days.

“We all love our tree-lined streets until a hurricane comes!” surmises Vanessa Baird-Streeter, a LIPA spokeswoman.

Towns and other local municipalities have also been preparing. Hempstead and Brookhaven have been gearing up for months in preparation of this potentially devastating hurricane season.

“We’re as prepared as a municipality can be,” says Hempstead Town spokesman Mike Deery. During hurricane season, he says, “we are constantly monitoring the weather.” This year the town has set up a debris-management system to cope with the aftermath of the storm, by moving downed trees, etc., to town and county property.

“Nobody knows what to expect,” explains Eileen Verity, coordinator of emergency preparedness at Catholic Charities, “Long Island could essentially be cut off from the mainland.”

Her organization will be taking care of those people with special needs, and ideally moving them to one of two locations, Holy Trinity High School in Hicksville and Kellenberg Memorial High School in Uniondale, which can handle about 1,500 people. Sometimes they won’t want to go, and they can’t be forced. She says they’ll try to start moving this population about 96 hours in advance of the storm, but she knows that is “not going to happen.

“I believe in paying attention to the warnings,” Verity says. “If they say it’s going to hit in four days, I start thinking about it hitting in four days. I don’t say, ‘It’s not going to hit, it’s not going to hit!’ When you hear the warnings, you listen. Don’t blow them off.”

Long Islanders have seen what Katrina and other big storms have done to people down South, and we’ve been through some bad ones up here, too. But do we ever learn?

“No, we never do!” remarks former Babylon Town Supervisor Rich Schaffer. “We never do.”

Schaffer’s point is one shared by weather experts, public officials and first responders.

“I think there’s an attitude problem among Long Islanders especially: ‘We’re in New York, nothing is going to happen to us, this is not Florida, this is not the West,’” cautions Beverly Poppel, vice president of Locust Valley-based PetSafe Coalition, a network of public and private organizations working to ensure others in the path of severe storms—animals—are also safe when faced with disaster.

Panico agrees, and believes many Long Islanders would scoff at evacuation: “The population here doesn’t have a true understanding of a major hurricane and what can occur from that.”

“Apathy by the public is a tough nut to crack,” says Mandia. “If people heed the warnings, there should be no reason that anybody loses their life, even in a major hurricane.”

After seeing first-hand the destruction left by Hurricane Hugo in Florida in 1989, Coch began sounding the alarm that New York is overdue. He has little sympathy for those who built homes in harm’s way.

He invokes the fate of Hog Island: “When you stick your tongue out at Mother Nature, she takes care of you.”