Suffolk OEM is making sure all the emergency generators are fueled, he says. They’ve already notified the police department and the county’s Department of Public Works to get more four-wheel-drive vehicles up and running. They’ve been setting up meetings with the American Red Cross, mobilizing additional manpower, and taking inventory of all their resources to identify what they have on hand and what they need. Suffolk OEM has also been communicating with other emergency agencies, such as the New York State Office of Emergency Management (NYSOEM), about “pre-disaster resources.”

The ultimate response to Earl and other potential disasters is the fruit of a complex, multi-layered process requiring precision coordination between myriad local, state and federal agencies. (In fact, our interview was cut short in order for Williams to join the NYSOEM, FEMA, and more than a dozen others on an emergency conference call about the storm.)

“We operate as a region,” he explained several minutes before the call. “We have very close ties with Nassau County, New York City, Westchester County, even New Jersey. We realize that we’re all in this together and we work as a team.”

Williams, who’s held his present title for the past six years and has more than 40 years’ experience in emergency services—joining the Valley Stream Fire Department at 17, also serving as an officer in the New York City Fire Department, among other positions—says a slew of new programs started in Suffolk in the wake of Katrina will also be utilized.

A fleet of “shelter buses” will pick up and transport residents in need of refuge to activated locations within Suffolk’s 121-shelter network, he explains. The buses will travel along pre-existing bus routes to ease confusion and accessibility. Another program in place, called JEEP—short for Joint Emergency Evacuation Program—will aid senior citizens who may need additional help. These residents have already filled out contact forms with the county listing their ailments and specific conditions. They will be contacted, and if requested, a police officer will visit them to assess what type of additional assistance they require, and take them to a shelter.

Suffolk County will also have several “Pet-Friendly Shelters” set up, where residents can stay, along with their pets. These will be established at the Suffolk County Sports Park in Central Islip, Suffolk County Fire Academy in Yaphank, and Suffolk County Community College’s Selden and Riverhead campuses, according to Suffolk County Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Chief Roy Gross.

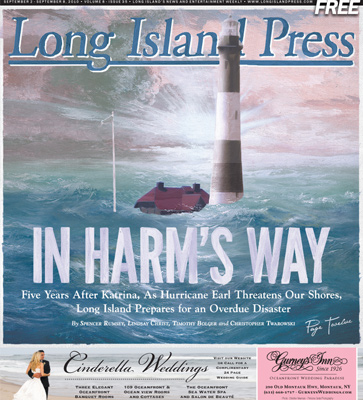

“This all occurred after Katrina,” explains Gross. “There are people that stayed in harm’s way because they would not abandon their animals and the shelters were not allowed to take animals. So people wouldn’t leave them. I know I wouldn’t. It’s like leaving your kids behind. And most people are like that—that’s part of their family.”

Suffolk County OEM Commissioner Joseph Williams at Yaphank's OPS command center.

“We’re going to treat [Earl] as a Category 1, Category 2 hurricane,” Williams continued. “If it does make the turn [further west], we can always back off on it. But as a precaution we have to do that. Our main concern here, for hurricanes, is Fire Island.”

As of press time, Williams had not given the order to begin evacuation efforts of the 32-mile barrier island, which was all but decimated in 1938. An armada of ferries would transport islanders—or at least, those who heed the call—off.

“We still have a certain amount of people who want to have their hurricane parties,” he said, half laughing. “We’ll tell them, ‘During the height of the storm, something happens, we can’t get back to help you. We’ll see you after the storm. So, if you’re going to stay, you’re there on your own.”

Yet as tough as it is to convince Labor Day party-goers on Fire Island to leave their expensive apocalypse shindigs, he explains, evacuating the rest of the affected communities is more of a fantasy.

“It’s virtually almost impossible to evacuate Long Island, especially Suffolk County,” he said.

That sentiment is reiterated by Dennis Malhowsky, director of public information for the division of New York State Office of Homeland Security and Emergency Services: “Everybody knows you cannot evacuate Long Island.”

It’s a foreboding reality wrapped inside an ominous situation—and it’s one also shared by emergency management personnel in Nassau.

End of the World

Inside Nassau’s fortress-like, subterranean Emergency Operations Center, rows and rows of numbered empty cubicles—enough for 36 people—stand ready along white cinder-block walls. An array of flat-topped desks faces a mammoth screen displaying weather information and updated reports that are disseminated to hundreds of people throughout the county. They’re flanked by other television screens tuned to various channels. The entire space is carpeted in blue with a drop ceiling for recessed lighting.

It’s no doubt far more comfortable than the cramped basement quarters of Winston Churchill’s war room, where he and his generals plotted the defense of England. Here, in what is arguably the most secure spot in the entire county, nobody’s going to bump their head on a low-hanging pipe if things are exploding outside. At the moment, the mood here is practiced calm.