by Spencer Rumsey, Lindsay Christ, Timothy Bolger and Christopher Twarowski

Imagine: The Atlantic Ocean extends north of Sunrise Highway, engulfing sections of the Southern State Parkway in some areas on the South Shore. Montauk Point and other communities along the North and South Fork are new islands. All bridges and tunnels in the New York Metropolitan area are closed. New York City’s transit system has ground to a halt. The Hudson and East rivers meet, splitting Manhattan into two separate islands. The Long Island Rail Road is shut down. Law enforcement and emergency services hole up indoors, or underground, unable to respond immediately to unfolding events and emergency calls. Countless fallen trees block roads, destroy homes and collapse power and communication lines. More than 1 million are without electricity. There are hundreds dead and more than a trillion dollars in damages.

National weather experts, emergency management officials, and the latest projections, such as recently updated flood maps, warn this is but a glimpse of the reality in store for Long Island and our region should we be hit with a major hurricane. And the grim reality is, we’re overdue.

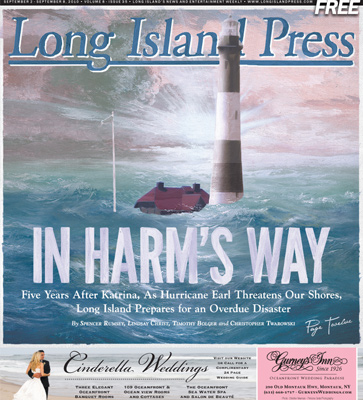

It’s been five years since Hurricane Katrina decimated New Orleans and parts of the Gulf Coast, with much of that region still in ruins from the blow. Now, at the height of the 2010 Atlantic Hurricane Season, weather experts warn our region is overdue for a major hurricane and predict a more active season than normal. The Weather Channel’s top hurricane expert recently ranked New York City second in its “Top Five Hurricane Vulnerable and Overdue Cities,” runner-up only to Miami. That means Long Island—pummeled in 1938 by perhaps the most notorious hurricane to strike New England, “The Long Island Express,” a Category 3—is at equally severe risk. With the first major hurricane of this season, powerful Category 4 Hurricane Earl, churning its way north along the Eastern Seaboard as of press time—and the similarly threatening Tropical Storm Fiona thrashing closely behind—Long Island prepares for the worst.

“We could be hit with a double-whammy here,” warned Suffolk County Executive Steve Levy at a hastily assembled Aug. 30 press conference to inform the public on the potential ramifications, “a storm at the beginning of Labor Day weekend, to be followed with another storm right after that.

[popup url=”http://assets.longislandpress.com/photos/gallery.php?gazpart=view&gazimage=6926″] Click here to view more photos of Hurricane Earl[/popup]

Click here to view more photos of Hurricane Earl[/popup]

“This is running the same route that we saw with Hurricane Bob back in 1991,” he cautioned—referring to a storm that resulted in more than half a million Suffolk County residents without power for about a week. “There is a great deal of damage that can come about from such a hurricane.”

He stressed to the Press: “We want the residents to take this seriously. Know where your shelters are, especially if you live on the South Shore of the Island. Make sure you have a place to go if you have to evacuate your home. Make sure that you have necessary first-aid available.”

As of press time, more than 1,000 workers from throughout the state have begun converging on LI to help the Long Island Power Authority (LIPA) restore electricity should Earl knock out power. The Weather Channel has stationed correspondents on Suffolk’s East End. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) has teams either on standby or on the ground, ready to assist, at potentially affected states. A hurricane watch and warning is expected to be issued by the National Weather Service for LI, currently under tropical storm watch.

Nassau County Office of Emergency Management (OEM) Commissioner James J. Callahan III, at his desk within the County's underground emergency OPS center (below).

Yet regardless of whether Earl or Fiona make impact or not, weather and emergency management experts stress it’s not a matter of if a major blast will strike Long Island, but rather when.

Prepared for the Worst

The unassuming building’s cobblestone façade and chipped, peeling paint of the outer sign demarking Suffolk County’s Office of Emergency Management (OEM) in Yaphank belies the facility’s critically vital importance. For it’s here, housed in an underground bunker encased within 14-inch thick walls, where the crucial, life-saving decisions will be made and implemented should the county and its 1.5 million residents face any variation of disaster: manmade or natural.

Goliath maps and charts plaster the walls. Some break down the county by town, village and street. Others outline flood and impact zones in the event of Category 1 through 5 hurricanes. Another tracks the path of Earl and Fiona, updated constantly with color-sequenced stickers. Projector screens and televisions hang from the ceiling. More than 50 work stations equipped with computers and phones stand at the ready in a sort of Doomsday control room, Suffolk’s Emergency Operations Center. Each console bears the name of the various agencies manning them, from local, state to federal.

The bunker has video satellite interface capability. Backup generators. Two mobile command vehicles. Even a portable antennae tower, should its main one be knocked out. In a crisis situation, such as a major hurricane making landfall, Levy himself would join the myriad of planners and emergency responders down here.

Nassau’s OEM center, presently situated in an underground “bunker” but slated to relocate to the recently opened Morrelly Homeland Security Center in Bethpage, is equally fortified and equipped (personnel are required to undergo a bone scan to even gain access). A similar scene would unfold there, too—with Nassau County Executive Ed Mangano holding court—should a disaster such as a major hurricane making landfall arise.

In addition to Suffolk’s Emergency Management Office, its Department of Fire, Rescue & Emergency Services is also housed in its complex. So is its communications center, an enhanced and reverse 911 facility—equipped to pinpoint the exact locations of callers, or notify residents en masse with lightning speed and precision, respectively. Dispatchers handle fire and EMS calls and coordinate units. They respond to myriad emergency calls and situations from here, 24/7, on a daily basis, regularly.

In addition to Suffolk’s Emergency Management Office, its Department of Fire, Rescue & Emergency Services is also housed in its complex. So is its communications center, an enhanced and reverse 911 facility—equipped to pinpoint the exact locations of callers, or notify residents en masse with lightning speed and precision, respectively. Dispatchers handle fire and EMS calls and coordinate units. They respond to myriad emergency calls and situations from here, 24/7, on a daily basis, regularly.

Yet things have been less than regular in the past several days.

“We’ve activated our 120-hour plan,” Suffolk OEM Commissioner Joseph Williams told the Press on the morning of Aug. 30 in his office at the facility—referring to a series of meetings, discussions, strategizing and planning sessions whereby his office runs down a comprehensive emergency “checklist” in preparation of an event, in this case, Hurricane Earl.