Classmates.com

Classmates.com

What the heck was that?

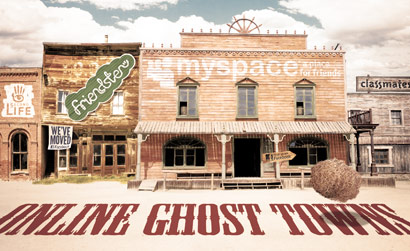

Classmates.com was the first social network to openly attempt to reconnect old friends. Randy Conrads founded the site in 1995, during the heyday of dial-up. (You may remember its Internet blitzkrieg of an ad campaign.) It worked on a paid-membership model, which means that while it could benefit from going viral, it wasn’t reliant on doing so like the other big networks. With the ad-based revenue of Friendster/MySpace, if hits are up you make more money, and if they’re down, you make less. Classmates.com can still make a monthly income off old users who no longer actively visit. “Classmates.com taught us that people will pay for something in which they find value…even on the ‘freenet,’” Conrads tells the Press.

What happened?

Joseph Monaco [a relative of one of the authors of this piece], when asked about his attempts to use Classmates.com, says he “found it hard to actually find and get in touch with people from high school”—as in it didn’t really do what it said it could do. Thus, per Michael Wolff’s functionality statement, it withered once there were competitors who could actually connect old friends. Conrads sold the site to United Online in 2004, a year before Facebook got off the ground and nabbed the market. From there the downward slope was severe, and not without reason, according to Wired columnist Clive Thompson. “With Classmates I thought, well, if you’re specifically aiming at older people…when those people die, if that was your user base, you’re dead in the long run.”

Where is it now?

It’s following the trend of certain other dead websites and trying to rebrand itself. Just this month it launched a new homepage, pitting itself as a nostalgia site where you can see photos, headlines, and full yearbooks from the year you graduated. The question now is whether a new image can overcome its social stigma as a defunct, obsolete endeavor.

Google Wave

Google Wave

What the heck was that?

On a list of overhyped things in recent memory, Google Wave falls somewhere between former USC quarterback Matt Leinart and Microsoft’s Kin phones. Google’s Vice President of Engineering Vic Gundotra promised “an unbelievable and powerful demonstration of what is possible in the browser” at Wave’s unveiling at Google’s annual I/O conference last year. Lars Rasmussen, Wave’s co-creator, described it as “what e-mail might look like if it was invented today.” These are pretty lofty goals. Wave aims to combine several forms of communication—instant messaging, chat rooms and e-mail—into a single space. Wave is viewed through a Web browser, so you could Wave (the verb form of using Google Wave) from any computer, much like logging into Gmail.

What happened?

Google Wave invitations were given out in a fashion similar to Gmail invites back in 2004. The first wave of invites went out to those in attendance at I/O the day Wave was unveiled. Slowly, they got invites, and random people got invites. Those people got invites, and slowly, invitations trickled out to everyone.

As demand for a Wave invite rapidly outstripped the meager supply, one place emerged as the go-to for early access to Google’s newest offering: eBay. Wave invitations began appearing on eBay, despite violating both the auction site’s and the search company’s terms of service. Some approached as much as $200.

This led to a particular scenario each time a Wave account finally landed in someone’s lap. First, joy: “I finally got my Google Wave invitation!” Then, disappointment: “None of my friends are on here yet.” And finally, confusion: “What the hell is this thing?” A staggered rollout of Gmail was OK because it could be used by one person and still send and receive e-mail with the rest of the world. Parceling out Wave invites meant you’d often find yourself sitting solo, waiting for someone to Wave at you (again, the verb of using Google Wave; sitting on a bench somewhere hoping someone waves at you is depressing). While you waited, you might take some time to peruse what Wave had to offer. At which point, extreme confusion would set in. Those several forms of communication Wave tried to unite wound up a jumbled mess that most resembled the chat room of the 21st century, and people stopped using chat rooms a long time ago for a reason—they just don’t work.

Where is it now?

Nearly everyone who encountered Wave had the same reaction to it, so as more people got a hold of an invitation, rumor became popular opinion became fact: Google Wave isn’t worth using. Word of this eventually got back to Google, and on Aug. 4, 2010, 434 days from its debut at I/O, the company ceased development. Anyone can still use Wave—no invite necessary—but Google has stopped working on the platform. Or, you know, making it usable.