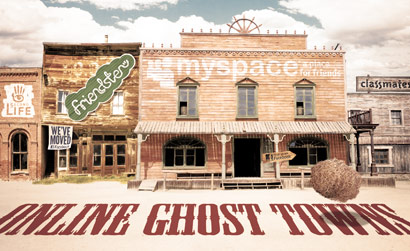

To read the stories of eight declining social networks, by Brad Pareso and James Monaco, click here

Before Facebook, before MySpace, before Friendster even, Keith was on MakeOutClub.com. This was back in 2000, a full decade ago now, the year George W. Bush was first elected into office as president, the year of the Y2K Bug. For Keith, MakeOutClub was the beginning of social networking.

“It had rudimentary features, but ultimately, users were encouraged to post a photo and communicate via instant message,” says Keith, a 34-year-old Greenlawn native who lives in Brooklyn today. “I think this was the first real opportunity for kids stranded in different parts of the country to connect with other like-minded individuals.”

It was a few years later—in May 2003—that Keith joined Friendster: a new form of social-networking site, one that offered more robust features than those found on MakeOutClub. You had to be invited to join, and once you were in, you built a profile—a home page with photographs, biographical information, likes and dislikes—and then, a circle of connections, “friends,” who also had profiles on the site. Those friends were encouraged to leave “testimonials” on your page and you were encouraged to reciprocate: to post short endorsements wherein you waxed poetic or nostalgic or enthusiastic or sarcastic or whatever about your friend. For example, one testimonial on Keith’s page (courtesy of his friend Heather) reads: “Keith has some dance moves and isn’t afraid to bust them out anywhere. Always working the scene and the ladies.”

Heather left that testimonial in June 2003. Back then, Keith was on Friendster pretty regularly. He had a lot of connections; his page was active. He used it to promote his band, to connect with acquaintances, co-workers, to meet girls. He used it because it gave him a look inside the otherwise private worlds of his friends.

“For the first time, I could get a real-time glimpse into the lives of other people,” says Keith. “Somehow, everyone else’s life seemed more fascinating, no matter what they were doing.”

Friendster was a seemingly instantaneous phenomenon, and the site’s visibility and popularity exploded into the mainstream. Virtually every high-circulation glossy lifestyle mag—including Time, Esquire, Vanity Fair, Entertainment Weekly, US Weekly and Spin—wrote about Friendster within a year of its launch (the site launched in March 2003, two months before Keith joined). At the time, Friendster looked like the future of the Web: In 2003, Google offered Friendster’s owners $30 million to buy the site, but they weren’t interested: They wanted Friendster to be the next Google, to be bigger than Google.

Friendster’s success inspired countless competitors, most of them dead on arrival—Tribe.net, Orkut.com, Gruuve.com, Netfriendships.com—and, of course, a live one. MySpace.com debuted in January 2004 and within a few short months, it had stolen much of Friendster’s audience: On March 1, 2004, MySpace surpassed Friendster as the No. 1-ranked social networking site in terms of page views, according to Nielsen NetRatings.

Keith remembers that time. He remembers watching his friends migrate away from Friendster, over to MySpace. And he too felt his attention begin to wander and wane.

“As my own friends started using MySpace, it was inevitable,” he says. “There were some holdouts, but if you wanted to feel ‘connected’ and not out of the loop, then you had no choice.”

At first, Keith remembers, people would go back and forth, keeping active on both sites. But soon, people just…stopped going to Friendster. They stopped updating their profiles, stopped cultivating new connections. They moved on.

“I somehow felt sorry for the people that didn’t jump ship,” says Keith. “I started feeling sorry for the site. I felt like I was abandoning a friend.”

Today, Keith does not know anyone else in the world who still uses Friendster. All of his friends are long gone, their profiles shut down or abandoned. Some old pictures remain, some old testimonials. But no people. They moved to MySpace for a little while…until that site suffered a fate very similar to the one it dealt Friendster. Now that place is kind of abandoned, too. Now they’re all on Facebook. Friendster, though? Well, it’s still there, but Keith can’t figure out how it stays in business. Or why. Still, he checks in from time to time. He can’t help himself.

“I sometimes do for nostalgia because it’s like a period of my life frozen in time,” says Keith. “I still get birthday-alert e-mails and other promotional e-mails from them. So as a gag I sometimes post those Friendster birthday alerts to Facebook. People laugh because to them it represents a much earlier period in their life that has been long forgotten.”

Social-networking sites are as old as the Internet. In the early days, there were things like Listserv, Usenet and bulletin board services (or BBS). Bigger than all those combined, America Online (AOL)—which at one point was virtually synonymous with the word “Internet”—featured many of the elements that would eventually come to be associated with social-networking sites: lists of friends (or “Buddy Lists”), chat rooms, “channels,” which were landing pages for specific topics, and customizable home pages.

Soon after that came sites like Geocities, Tripod and Angelfire: online communities that provided to subscribers personal Web pages and simple, user-friendly functionality. Later, the heavily promoted Classmates.com encouraged users to reach out to and engage with old high school and college acquaintances by providing a place for those people to reconnect and a forum for them to interact. Dating websites like Match.com and Nerve Personals featured user profiles similar to the ones that would eventually become the Friendster/MySpace/Facebook template. And there were early iterations of social networking such as SixDegrees.com, Yahoo Groups, SocialNet.com… There was even Keith’s first foray into social networking: MakeOutClub.

There were lots of these sites. And some of them even still exist today, in some form or fashion. But none of them have a future. None of them really even have a present.