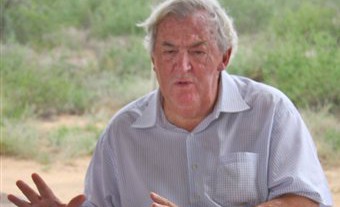

In this 2008 photo provided by the Turkana Basin Institute, paleoanthropologist Richard Leakey discusses the evidence for human evolution over a collection of hominin fossil casts at the Turkana Basin Institute's Ileret research facility in northern Kenya. (AP Photo/Turkana Basin Institute, Bob Campbell)

Richard Leakey predicts skepticism over evolution will soon be history.

Not that the avowed atheist has any doubts himself.

Sometime in the next 15 to 30 years, the Kenyan-born paleoanthropologist expects scientific discoveries will have accelerated to the point that “even the skeptics can accept it.”

“If you get to the stage where you can persuade people on the evidence, that it’s solid, that we are all African, that color is superficial, that stages of development of culture are all interactive,” Leakey says, “then I think we have a chance of a world that will respond better to global challenges.”

Leakey, a professor at Stony Brook University on Long Island, recently spent several weeks in New York promoting the Turkana Basin Institute in Kenya. The institute, where Leakey spends most of his time, welcomes researchers and scientists from around the world dedicated to unearthing the origins of mankind in an area rich with fossils.

His friend, Paul Simon, performed at a May 2 fundraiser for the institute in Manhattan that collected more than $2 million. A National Geographic documentary on his work at Turkana aired this month on public television.

Now 67, Leakey is the son of the late Louis and Mary Leakey and conducts research with his wife, Meave, and daughter, Louise. The family claims to have unearthed “much of the existing fossil evidence for human evolution.”

On the eve of his return to Africa earlier this week, Leakey spoke to The Associated Press in New York City about the past and the future.

“If you look back, the thing that strikes you, if you’ve got any sensitivity, is that extinction is the most common phenomena,” Leakey says. “Extinction is always driven by environmental change. Environmental change is always driven by climate change. Man accelerated, if not created, planet change phenomena; I think we have to recognize that the future is by no means a very rosy one.”

Any hope for mankind’s future, he insists, rests on accepting existing scientific evidence of its past.

“If we’re spreading out across the world from centers like Europe and America that evolution is nonsense and science is nonsense, how do you combat new pathogens, how do you combat new strains of disease that are evolving in the environment?” he asked.

“If you don’t like the word evolution, I don’t care what you call it, but life has changed. You can lay out all the fossils that have been collected and establish lineages that even a fool could work up. So the question is why, how does this happen? It’s not covered by Genesis. There’s no explanation for this change going back 500 million years in any book I’ve read from the lips of any God.”

Leakey insists he has no animosity toward religion.

“If you tell me, well, people really need a faith … I understand that,” he said.

“I see no reason why you shouldn’t go through your life thinking if you’re a good citizen, you’ll get a better future in the afterlife ….”

Leakey began his work searching for fossils in the mid-1960s. His team unearthed a nearly complete 1.6-million-year-old skeleton in 1984 that became known as “Turkana Boy,” the first known early human with long legs, short arms and a tall stature.

In the late 1980s, Leakey began a career in government service in Kenya, heading the Kenya Wildlife Service. He led the quest to protect elephants from poachers who were killing the animals at an alarming rate in order to harvest their valuable ivory tusks. He gathered 12 tons of confiscated ivory in Nairobi National Park and set it afire in a 1989 demonstration that attracted worldwide headlines.

In 1993, Leakey crashed a small propeller-driven plane; his lower legs were later amputated and he now gets around on artificial limbs. There were suspicions the plane had been sabotaged by his political enemies, but it was never proven.

About a decade ago, he visited Stony Brook University on eastern Long Island, a part of the State University of New York, as a guest lecturer. Then-President Shirley Strum Kenny began lobbying Leakey to join the faculty. It was a process that took about two years; he relented after returning to the campus to accept an honorary degree.

Kenny convinced him that he could remain in Kenya most of the time, where Stony Brook anthropology students could visit and learn about his work. And the college founded in 1957 would benefit from the gravitas of such a noted professor on its faculty.

“It was much easier to work with a new university that didn’t have a 200-year-old image where it was so set in its ways like some of the Ivy League schools that you couldn’t really change what they did and what they thought,” he said.

Earlier this month, Paul Simon performed at a benefit dinner for the Turkana Basin Institute. IMAX CEO Rich Gelfond and his wife, Peggy Bonapace Gelfond, and billionaire hedge fund investor Jim Simons and his wife, Marilyn, were among those attending the exclusive show in Manhattan’s Chelsea neighborhood.

Simon agreed to allow his music to be performed on the National Geographic documentary airing on PBS and donated an autographed guitar at the fundraiser that sold for nearly $20,000.

Leakey, who clearly cherishes investigating the past, is less optimistic about the future.

“We may be on the cusp of some very real disasters that have nothing to do with whether the elephant survives, or a cheetah survives, but if we survive.”

Copyright 2012 The Associated Press.