ON THE ROAD TO SOMEWHERE

The future hasn’t happened yet. Here’s a snapshot of a few of the big ticket items already slated for the Island−some in the works and others just pie in the sky:

Long Island only gets 1 percent of its freight delivered by train, compared to almost 20 percent on average in other regions of the country. Right now lumber yards on the Island get their building materials by trucks coming through New York City. That situation could change this summer when the Brookhaven Rail Terminal, a privately run consortium under the auspices of U.S. Rail of New York, begins operating its new rail freight intermodal facility in Yaphank off the Long Island Expressway near Exit 66. Using the LIRR’s Greenport Main Branch Line, the facility could handle up to a million tons a year.

Just a couple of weeks ago Michael Polimeni, chief operating officer of Polimeni International, a developer based in Garden City, met with members of the New York State Department of Transportation in Albany to discuss a project that would also drastically alter traffic patterns on Long Island in the future. If his firm gets the green light, it would oversee construction of an 18-mile, high-speed tunnel under Long Island Sound connecting Syosset and Rye, employing technology now being used in the LIRR’s East-Side Access project under the East River. The difference is that this tunnel project wouldn’t use a dime of public money. Polimeni’s $12-billion tunnel would be about privately run, with tolls set at about $25, and an estimated volume of 80,000 vehicles a day, if not more, if it opens as planned by 2025.

All he wants now, he insists, is the state to give his company the sole rights to pursue the project before his firm conducts any further work. “Everyone is very receptive to this project, which is still in its infancy,” Polimeni says. “If we can show a viable study, then it’s a whole different story. But I can’t pull the trigger on that until I know it’s mine.”

Developer Gerald Wolkoff says if he got the permits this Saturday he could start Sunday on his 9,000-unit Heartland Town Square proposal slated for Brentwood. With its apartments, office towers, stores, restaurants and walkways, the multi-million-dollar project could be huge, both in terms of tax revenue and its impact on nearby county retail outlets and neighborhoods. Islip Town Supervisor Phil Nolan has worked out an agreement with Wolkoff, who has been beating the drum for this “suburbanopolis” for almost a decade, to construct it in three phases, so the town can measure the impacts along the way and apply the brakes if necessary. “I’m hopeful we’ll get it started this year,” Nolan tells the Long Island Press.

Wyandanch Rising, an ambitious redevelopment plan for one of Suffolk’s hardest hit communities, is still on track, public officials say. The county continues to fulfill its commitment to Babylon Town to help lay new sewer mains down Straight Path and waive $11 million in connection fees to enable multi-story development in a commercial area near the present train station. Eventually there will be a new public square and town houses as well as retail establishments. The town says it plans to announce the redeveloper by the end of this month.

The Nassau Hub, once the site of Mitchell Field, and now basically a parking lot wasteland surrounding the Coliseum across from Hofstra University, is back in the news—again—because the county wants to put a $400-million bond issue on the ballot in a special election this August. The money would pay for renovating the run-down home of the Islanders and for a new ballpark for a minor league team. The catch is that the Nassau Interim Finance Authority, now in control of the county’s finances since its budget is reportedly $176 million in the red, has the last word on any new borrowing.

Another problem with the Hub is that although the county owns the land, the Town of Hempstead controls the zoning. Many people with deep pockets have coveted the location but the county has stipulated that any new project would have to include a new Coliseum, inspiring developers to think big so their profits could cover the additional cost. Charles Wang’s solution would have been to build The Lighthouse, so tall “you could see it in Ohio!” joked Koppelman, who had done a study of the area in the 1990s. To mitigate concerns about traffic congestion, the county has consistently made connecting new mass transit to the Hub a planning priority. But now Nassau doesn’t even want to continue subsidizing Long Island Bus. “They’ve been looking at Nassau Hub for years yet they refuse to fund their bus system,” says Ryan Lynch of the Tri-State Transportation Campaign. “I find that very, very odd.”

To Koppelman, the county’s contradictory move is understandable. “The basic problem with transportation…is that the State of New York and the federal government never put up the money that’s required to really do the job. Buses and trains must be heavily subsidized. So you see in Nassau County, where they’re running several hundred million dollars in the red, the first thing that County Executive Ed Mangano wanted to cut out was support for more than half of the bus routes. So instead of moving toward more mass transit, we’re moving in the other direction.

“In Suffolk County,” observes Koppelman, who has extensively studied the issue, “buses have not worked too successfully for a simple reason: We don’t have the density of people per square mile. So the result is that on many of the routes you have to wait for an hour or more….That’s not how you encourage bus ridership! Unless Suffolk County government indicates they’re willing to increase subsidies, there’s no way to improve service.”

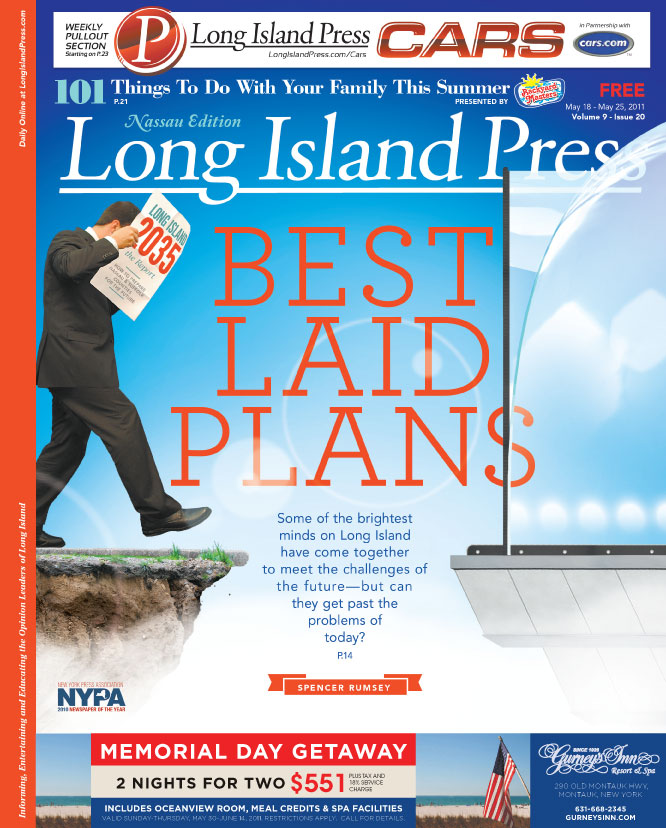

From the “transportation goals” section of the LI 2035 Sustainability Plan comes this conclusion: “The future of Long Island depends on investment in its existing transit network and a thoughtful expansion of the transit system.” No price tag is mentioned. In the mean time the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, which funds the Long Island Rail Road and subsidizes public bus service, is billions of dollars short on the remainder of its current capital plan. And Long Island businesses are still boiling mad about having to pay the MTA payroll tax, imposed in 2009, so finding a new revenue stream for mass transit will be a rough ride indeed.