Errors of Consequence

There are two important factors in making a match: the missing persons report filed by police and the autopsy report filed by the coroner. Both go into the National Crime Information Center (NCIC) database, available only to law enforcement. The system matches information between departments including John Does and missing persons reports—that is, if both reports are entered into the database correctly. One transposed number or a simple formatting error could prevent a match from being made.

Janice Smolinski of Connecticut, whose son Billy has been an endangered missing person for more than six years, knows this all too well.

“In our search to find our son, we encountered a Pandora’s Box,” Smolinski testified at a congressional hearing. “And when we opened it, we unleashed the nightmare plaguing the world of the missing and the unidentified dead.”

When Billy disappeared on August 24, 2004, he was 31-years-old. Since then, tips have come in claiming he was murdered and his body allegedly in different locations, all checked out by law enforcement, but none of them have led to Billy’s whereabouts. His case has been featured on the Investigation Discovery show Disappeared in 2010. Smolinski tells the Press multiple samples of her son’s DNA were lost.

“From my experience with my son, the DNA was collected, but it wasn’t [put into the database properly] and I was told by a coroner out west that if isn’t you might as well just throw it away,” says Smolinski.

Smolinski was fortunate enough to find a coroner who was able to also give her the details on her son’s disappearance listed in the NCIC database. It was wrong.

“You can see that across the board that this is not working,” says Smolinski. “And we’re not unique. This is happening all over. We just happen to question a little more and get answers. My son’s story is being told because of all the disconnects.”

Smolinski is lobbying to get the Help Find the Missing Act—or Billy’s Law, named after her son—passed, legislation which would require the FBI to share information, excluding sensitive and confidential data, with the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System (NamUs)—a database similar to NCIC, but lacking much of the latter’s information— that is accessible to the public.

Billy’s Law would authorize $50 million in incentive grants to encourage law enforcement to share information on missing people and unidentified remains. The bill was passed by the House last year, but didn’t pass in the Senate before that session of Congress ended, and therefore must be reintroduced in the new session.

Smolinski says the major problem is that there are 17,000 different law enforcement agencies nationwide and no central place, other than NamUs, to input homicide and missing persons information that is accessible to everyone, and it’s use isn’t mandated.

“Each law enforcement is territorial, and they have their own databases,” says Smolinski. “But the Internet doesn’t connect between their computers and that’s why NamUs comes in handy because this is a central database. I found one case where the family was looking for their son for months and he was in the medical examiner’s office with a tag on his toe.”

It’s happened in the past. One of Joel Rifkin’s victims, a 29-year-old Stony Brook woman, was reported missing in Suffolk County, but her body lay in a NYC morgue for more than an year before she was identified.

Tony Evelina, the Long Island director for the Doe Network, a national volunteer organization that helps match John and Jane Does with missing persons via the Internet, and helped build the NamUs public database.

“We’re trying to push on police departments, county coroners, state coroners, and let them learn how to use NamUs as well as NCIC,” says Evelina, who spends much of his personal time investigating forgotten cases of the missing and unidentified. “A lot of unidentified, especially in NY, never get into NCIC.”

Making matches also depends on the local law enforcement agency you are dealing with. Different states, especially, can have different methods of handling crimes.

“The government told me that some—which is just really hard to think about—that some law enforcement and medical examiners in this country don’t even have Internet access,” says Smolinski. “In this day and age.”

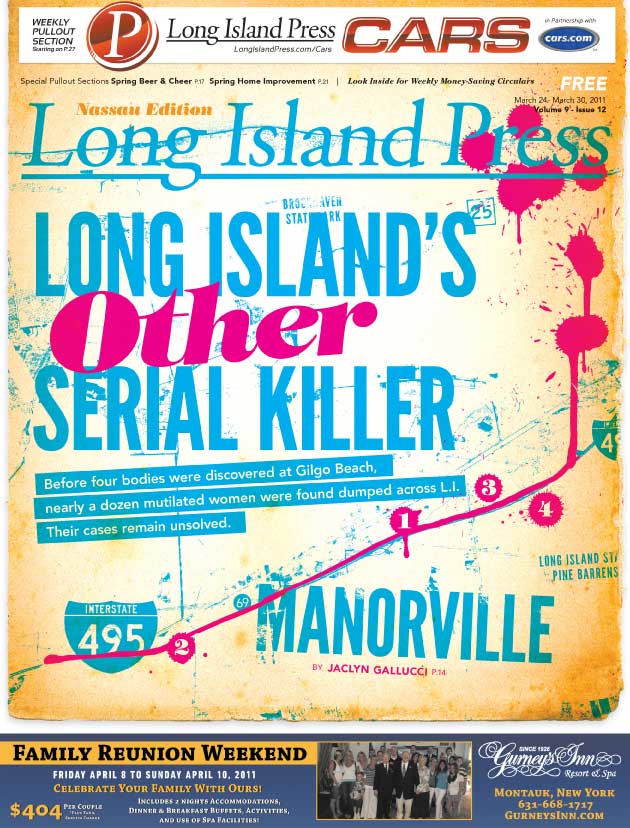

Many of those who have become aware of the disconnects in the system research unsolved cases using the little information available to them and come up with their own theories and sets of questions: Are these murders all related? Is there another serial killer in disguise on Long Island?