For The Birds

Another mammoth tract of trees felled by the Friends once stood near the exit of the preserve, to the side of a smaller building most recently known as the Dog Project, across the street from large, open fields of lawn.

Throughout the past several months, out of the sawdust and remnants of the latter downed trees, a wooden structure, which looks sort of like a ramshackle deck, has emerged, enclosed by loose fencing and most recently, concrete walkways and slabs.

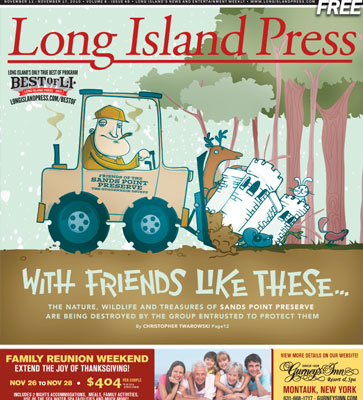

Gone But Never Forgotten: When the Friends of the Sands Point Preserve's first attempts to chop down a rare, beloved, century-plus-old Copper Beech Tree at Sands Point Perpetual Nature Preserve were thwarted by the county, they dug post holes, piled fill and went on with their plans for an "Outdoor Learning Center" anyway.

According to the minutes of Friends’ board of directors meetings reviewed by the Press, this chop job was necessary in order to make room for an “Outdoor Learning Center,” to be named in honor of a board member’s late brother. Its namesake donated $25,000 to the Friends in his memory.

“The area next to the Dog Project is being cleared,” read the minutes. “The idea is to create a Kids Exploration Center unique to the preserve that would attract toddlers to tweens.”

The project has been mentioned in documents since May 27, 2009. But before the Friends could make it a reality, there was one very large and very old problem standing in their way: A rare, 100-plus-year-old copper beech tree, a species known for its light gray bark, purple-to-copper foliage and visually attractive trunks.

It is, perhaps, the most noticeably absent, and most missed tree of longtime county park goers.

The Friends’ first attempts to rip it apart was thwarted by the county several months ago after it was alerted to their plans. But, instead of moving their project to, say, anywhere else on the 200-plus acre property, they dug postholes along the tree’s base and piled fill on top of its roots. Construction, utilizing heavy machinery and equipment, which further compacted the soil, proceeded as planned. The Friends ultimately attributed the tree’s demise to a subsequently fallen limb as proof of its weakness and danger to children who’d eventually use the center (forget the fact it’s built inches from the preserve’s exit, its busiest roadway, critics point out). The disruptions and stresses were ultimately a death sentence, say veteran preservationists.

Workers used chainsaws, sledgehammers and a crane to gut and finally topple the historic tree.

“Beech trees as a whole species take soil compaction around them very poorly,” explains Allan Lindberg, a retired natural areas manager who worked in Nassau County preserves for roughly 35 years. “The addition of soil mounding around them, basically, is nothing more than a slow killer of trees.

“That tree there, obviously, being very old, is historic to the property and it is a specimen and something that you’d want to keep,” he says. “It could have been a record tree for its species on the Island.”

Despite a condition called heart rot, which is the decaying of the interior of a tree, Lindberg insists it was in fairly sound health at the time it was butchered, having inspected it with Mills earlier on.

So, despite surviving two World Wars, roughly a half dozen major hurricanes, and 18 presidencies, the tree could not weather the Friends. On a steamy late August afternoon, the Press witnessed its fate—this time delivered by the hands of skilled professionals rather than untrained 20-somethings.

Workers attacked it first with chainsaws, ripping through its limbs as if a piece of toilet paper shoved in a blender; sawdust everywhere. Then they hacked at its base—several feet in diameter. When its gutted skeleton still wouldn’t cave, workers rammed it repeatedly with a crane until it did.

Now, freshly laid concrete now serves as its headstone, erasing any evidence of a trunk once tattooed with the initials of lovers who laughed beneath the shade of its lofty purple leaves.

Mills sees the assault on the copper beech tree as merely further evidence of the Friends’ utter disregard for nature and dismisses the Friends’ excuse that they consulted an arborist before their slashings.

“Instead of caring for the tree in a proper manner to try and preserve it, their idea was, ‘Oh, well, we’ll just do whatever we’re going to do, and whatever happens to the tree happens to the tree.’”

The Friends of the Sands Point Preserve have erased all evidence of the light gray, purple-copper-leafed gentle giant.

The mass clearing of trees and vegetation also increases instances and the speed of erosion—evident at several sections of exposed earth once the home to photosynthetic anchors. Most dramatic, the Press observed, is the wear dissolving a now-bare portion of cliff face behind Hempstead House, where bulldozers rest and the ground is crackling and buckling beneath its outer terrace.

“I would say this borders on the criminal,” assesses a shocked Richard Schary upon surveying the crumbling hillside. “This should be reported; this is a violation of coastal regulations. Because all this dirt is eventually going to end up in the Sound and this cliff’s just going to collapse.”

Also eroding rapidly is the area earmarked for the Friends’ amphitheater. The land slopes downward, and due to the loss of trees and vegetation, rainwater now cascades toward the cliffs, transforming what resembles an open field into a steady stream of water during each storm, pushing outward toward the sea and melting away the precipice into a large gully off its side. Someone tossed bales of hay as a makeshift dam here in an apparent and futile attempt to stop it.

“This is a violation of every engineering and landscaping principle I know,” he says.