John Montone, who was in the shadow of the South Tower when it fell.

“This is obviously a terrorist attack.”

At first, Harris did not know what had actually happened. He thought maybe it was a replay of the first plane, or perhaps even computer animation. The fireball was unmistakable, though.

“I asked him, ‘Did another plane hit the other tower?’” says Harris. “The caller said no, that he just saw another explosion.”

But when the tape was replayed on the television, Harris had enough evidence to make a leap of faith.

Montone was listening in his truck as he barreled down the West Side Highway, and heard the interaction between Harris and the caller. And he heard Harris take the chance.

“This is obviously a terrorist attack,” said the veteran news man over the air, to millions of terrified listeners. He was one of the first to say it on the air, anywhere.

“That’s when I knew I was going into a war zone,” says Montone.

From her rooftop, Fleischer did not see the second plane, but instead saw the tremendous explosion of fire, steel and glass.

“I thought, initially, one of the planes that had been going around had been sucked into something,” says Fleischer.

She leans forward and her hands become animated as she recounts the impact. “It was so weird, because when the plane hit, things came out of the building. It was broken glass, and the glass and the sun, the juxtaposition of this horror, and then what looked like diamonds falling from the sky was a really strange image.”

The stakes were raised substantially in the newsroom, and throughout the day Mason had to help his staff balance their emotions and the tasks at hand. They broke into groups. Some watched the TV screens, others monitored wire reports. The phones, says Mason, were crushed with calls. Sorting through the flood of information would be a major task. Mason would periodically retire to his office, away from the fray, to listen to what was going over the air.

“Our primary thrust is to have the best information possible coming out of the dashboard speakers,” says Mason.

Downtown, Montone had hurriedly parked his truck on Broadway and ran to the Trade Center to interview people who were streaming out of the crippled buildings. After he had completed some interviews, he realized that his cell phone, like most others, could no longer get a signal. He ran to the truck, where he had a phone hard-wired, but that was also out of commission.

“I’m thinking, ‘I need a phone,’” says Montone. “And there was a record store on Broadway at the time called, ironically, Record Explosion.”

Montone charged into the store, which he had visited in the past, and asked the people working there if he could use the phone. The recorder he was using at the time had an external speaker, and once he was on air, Montone hit the play button and held the receiver to the speaker. He was suddenly in the Dark Ages of radio.

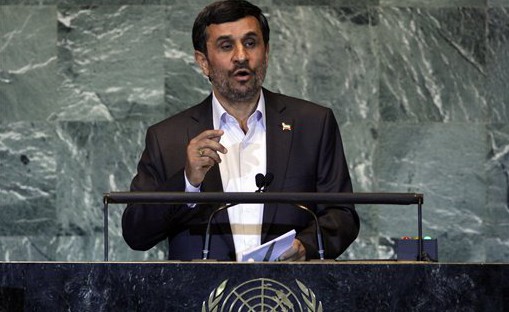

Former WINS Executive Editor Mark Mason

The report ended when Harris said breaking news was coming from Washington, D.C., and Harris told listeners that Montone was going back to the Trade Center. He ran back down, and on Day Street, near the Century 21 building, Montone found a doorman with a thick Eastern European accent and asked him what he had seen.

The doorman answered his questions, and then cautioned him, “‘Watch out, there is shit falling,’” Montone remembers.

Then Montone looked up to the burning tower, and suddenly, he was angry.

“You sons of bitches. Look what you’ve done,” he thought to himself as he set out once again to find people to tell their stories.

As he reached Broadway, and thousands ran from the buildings, a line of firefighters made their way to the World Trade Center. For Montone, it became the lasting image of that day.

“These guys were all young guys, and I didn’t think much of it at that time, but these guys were marching into probably what was the end of their lives,” he says.

Montone found a woman who had been on a bus coming out of the Battery Tunnel when the second plane had hit the South Tower. He started to interview her. Suddenly, the woman screamed, “It’s falling!”

Montone heard what he said sounded like a big stick breaking.

The interview would be cut short.

“Oh my God! The Building Fell!”

Lee Harris was doing his best to keep the news flowing smoothly through the 1010 WINS anchor chair. Also on shift were Faherty and Judy DeAngelis, who had yet to anchor since the second plane had been piloted into the South Tower.

Harris was speaking between reports from Mevorach, who had reached lower Manhattan despite the closing of all roads coming into the city, Montone, Fleischer, other special bulletins and guests.

It was almost 10 a.m., one hour and 14 minutes since the first plane had slammed into the North Tower.

“There was a sort of lull in the action, when nothing horrible had happened for about 10 minutes,” says Harris. “We were assembling all of our reporters for a round-up at the 10 o’clock hour. I was essentially killing time with Joan, then [came] a bloodcurdling scream that has been heard round the world by now, as the first tower came down.”

“Oh my God! The building fell!” screamed Fleischer into her phone as the building turned to dust before her eyes.

Fleischer has never listened to the tape of her reaction to the building’s collapse. She only remembers it because she has read her own words in articles just like this one. She thinks she should have been more articulate, and not so—as she puts it—“valley girl.”