Since the explosion of the Internet, people—even those suffering from a harmless headache or fever—have been turning to Google and health information websites to learn what’s ailing them, oftentimes discovering dubious prognoses that have them scampering to their doctors with faulty evidence they think proves they’re severely ill, or worse.

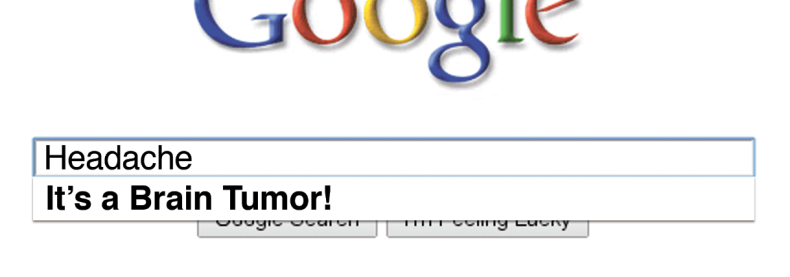

Internet users are increasingly typing “headache” into search engines to learn they might be suffering from a brain tumor. Or they’re searching “fever” and being told it’s a symptom of Leukemia. Chest pain equals a heart attack. Muscle twitches must be ALS (or Lou Gehrig’s Disease). Bug bites are surely a flesh-eating staph infection.

Computer-aided self-diagnoses can lead to anxiety and a whole-hearted acceptance of whatever unfounded prognostication is blaring from the screen. Searchers are contracting something, all right—recently dubbed “Cyberchondria,” it’s the Internet-equivalent of hypochondria—and the number of infected is continuing to grow.

A 2008 study by Pew Research Center found that 75 to 80 percent of people surveyed have looked online for medical information.

A study of Cyberchondria by Microsoft, also in 2008, found that the Internet has the potential to increase the risk of medical concerns and can lead to “unnecessary anxiety, investment of time, and expensive engagements with healthcare professionals.”

The study also discovered that an online search for causes of a headache listed “brain tumor” as the culprit 26 percent of the time, which had the same number of results as the more likely cause—“caffeine withdrawal.”

“It scares people to death,” says Susan Hirsch, a personal care doctor at North Shore-Long Island Jewish Medical Center in Manhasset.

In the past decade, doctors have seen a large number of patients educating themselves via Internet search engines before visits, she says. She’s surprised when people don’t come in with prior information about their symptoms.

“Sometimes they have an open mind,” she says. “They say ‘I read about it—I know I’m not a doctor—but here’s what is scaring me.’ But other times they really cling to what the Internet says they have and they just won’t let go of it.”

Others go to the extreme and take the advice given on the Internet over trained medical professionals.

One extreme example, Hirsch tells the Press, is a 60-year-old male patient of hers. He suffers from heart problems and was prescribed Plavix—“which basically is a life-saving medication,” Hirsch says—but the man decided to stop taking the once-daily medication because he learned on the Web that it causes bleeding.

He recently had a heart attack.

“It might say ‘Warning’ on the Internet,” says Hirsch, “but the point is you have to check with your doctor.”

Another patient, this one suffering from ear problems, visited Hirsch and admitted that she tried to treat herself by sticking a clove of garlic in her ear—because the Internet said to do so. Hirsch treated her and advised against aural garlic therapy.

There can be some benefit to patients educating themselves, admits Hirsch, but some take it too far—and that can be dangerous.

The moral of the story: Trust your doctor, not the computer.

“You don’t want to get too defensive,” Hirsch says, “but the patient has to be able to trust you at a certain point.

“I’m still the one with experience,” she adds.

As seen in the Aug. 16 – Aug. 22 issue of Long Island Press