John Caruso points to an orange pushpin on a poster-size map propped up against a wall inside Massapequa Water District’s conference room.

Unlike the charts one might expect to find in the headquarters of a water district—perhaps delineating the mileage of its distribution system or the locations of its pumping stations—this map and several others bear massive, multi-colored splotches smeared across their tops.

Some also have dates.

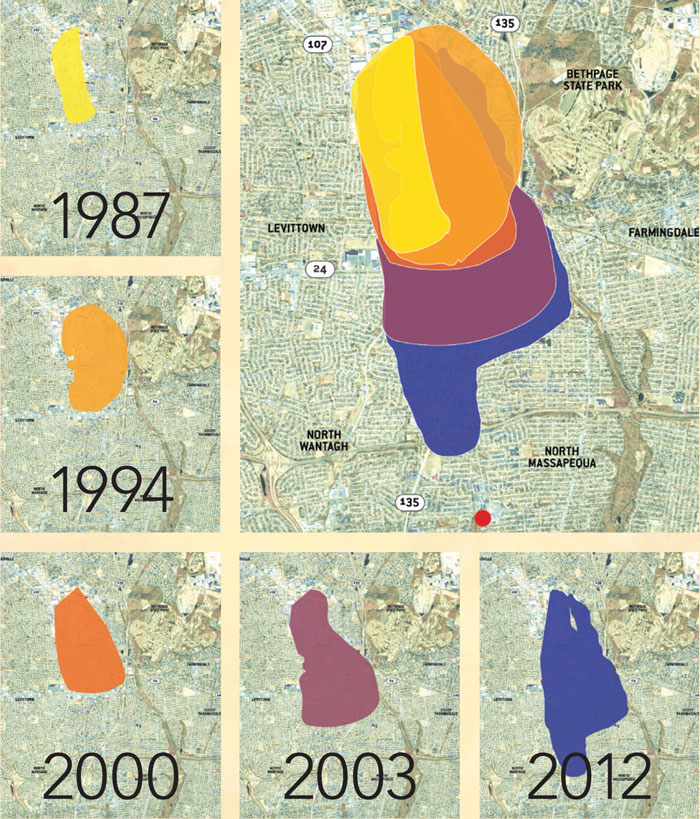

“1987 Plume” marks a yellow knife-shaped stain on one, spanning about a mile just north of Hempstead Turnpike in Bethpage. “1994 Plume” shows a green blob, more than double in size. Six years later it’s shaded red and has become even more gigantic. The “2003 Plume,” a blue spot that’s tripled in girth, blots out the turnpike and a long stretch of the Seaford-Oyster Bay Expressway. By 2012, the purple mass encompasses about four and a half miles, overrunning the Southern State Parkway and spilling into North Wantagh.

Caruso’s orange pin marks its southern-most edge, where he says, chemicals associated with the ever-creeping ooze, such as Trichloroethylene, or TCE—classified as a human carcinogen by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)—were detected in the groundwater earlier this year.

“We had the Navy install a monitoring well here, and that monitoring well now shows that at 150 feet, the Grumman plume is there,” he tells the Press. “That’s within eight-tenths of a mile of our wells.”

CLICK HERE FOR FULL MULTIMEDIA PACKAGE, INCLUDING VIDEO, PHOTOS AND TIMELINE.

By “Grumman Plume,” Caruso is referring to a roughly 4.5-mile long by 3.5-mile wide underground pool of toxic chemicals emanating from the former Grumman Aerospace Corporation and Naval Weapons Industrial Reserve Plant (NWIRP) sites in Bethpage, which for the past several decades, has been bleeding south-southeast and contaminating public drinking water wells in its path.

Caruso, a commissioner of the Massapequa Water District (MWD) and a former Nassau County Department of Public Works deputy commissioner for water supply and sewers, is one of the plume’s most vocal and passionate critics. He’s been trying, in vain he says, for years to get regulators, namely the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC), to stop its southward migration dead in its tracks. Lately he’s been encouraging residents to contact Gov. Andrew Cuomo.

As the latest boring is proof, Caruso says, the plume is traveling much faster than the agency states, and he estimates Massapequa’s public water supply wells will become polluted within approximately four years. He wants the plume cleaned up once and for all, starting immediately, and the parties responsible for the caustic mess—Northrop Grumman Corp. and the U.S. Department of Navy; both named in state documents as Potentially Responsible Parties, or PRPs—to pay for it. Most importantly, Caruso can’t stress enough, is the need for the cleanup to take place now, before the toxic mess contaminates the drinking water wells supplying his district’s 46,000 customers.

Heading South: Time-progression charts mapping the South-Southeasterly spread of the toxic plume emanating from the former Grumman aerospace complex and naval weapons industrial reserve plant in Bethpage. (Source: Massapequa Water District)

The water commissioner holds especial disdain for the DEC’s current plan regarding water supply wells that may be hit in the future, which he says, is to allow the public water supply wells to first become contaminated, and then for the Navy or Grumman to pick up the construction and implementation costs of what’s called “wellhead treatment,” afterward.

Caruso slams the strategy—known as the Wellhead Treatment Contingency Plan—as nonsensical, overly costly and dangerous to public health and safety. The approach is a requirement of the DEC’s final 2001 Record of Decision on how to handle the bulk of the groundwater contamination plume, dubbed Operable Unit 2 (OU2).

“We do not want wellhead treatment!” he blasts. “What we want is the Navy and Grumman to stop the plume, by what is known as hydraulic containment… Why are we letting a perfectly good water supply get contaminated when it can be stopped?”

Massapequa Water District’s plan, which cost about $500,000 to devise and is still evolving, says Caruso, includes up to 12 extraction wells along the plume’s southern-most edge forming a hydraulic defense to suck up chemicals, pump them to a treatment facility and re-inject it back into the ground, post-decontamination. The estimated cost is $400 million over 30 years—cheaper, he says, than what it would be to perform wellhead treatment at all 25 wells that are in the plume’s path.

Jim Harrington, of the DEC’s Division of Environmental Remediation, defends the agency’s strategy, saying Massapequa’s proposal is too costly and too difficult to implement. He also disputes its effectiveness, and questions whether the chemicals discovered at the Southern State Parkway well are the Navy-Grumman plume.

“We don’t want their wells to become contaminated,” he tells the Press. “We’ve done what we think is the best selection to prevent that. There is some potential that eventually one or more of the Massapequa wells will be impacted slightly. There is no certainty that it will be impacted by any great degree.”

Caruso isn’t alone in his demands, his frustration or criticism. Officials from several other water districts within the plume’s path have also been sounding the alarm about the oncoming disaster set to pollute their consumers’ drinking water—which could ultimately affect more than 200,000 residents, according to Caruso.

“Let’s stop it where it is. Let’s not let it continue to migrate further south impacting more wells, and possibly the Great South Bay,” says Len Constantinopoli, business manager and 23-veteran of the South Farmingdale Water District, the next Nassau municipal public drinking water supply in the plume’s crosshairs.

He tells the Press South Farmingdale is ready, at least for Round One. With the help of U.S. Sen. Charles Schumer (D-NY), who’s been actively involved in the issue, says Constantinopoli, the district successfully negotiated $14.5 million from the Navy to pay for a wellhead treatment facility at one of its plants, which opened last year.

“We will be impacted in the very near future,” he says, ominously. “It could be today.”

Constantinopoli and Caruso are not the only ones up in arms.

“They’re saying they can get 90 percent capture of the plume,” Bill Varley, president of New York American Water, says of the DEC’s latest Proposed Remedial Action Plan (PRAP), which was presented to several hundred residents for public comment at a heated, near-standing room only session at Bethpage High School June 12. (The public comment period on efforts to clean up what’s called OU3, ends July 30.) His company operates wells in Levittown and parts of Massapequa, among other municipalities, and presently has one temporary treatment facility in place that the Navy paid for.

“Ninety percent’s not acceptable,” he says. “You got to get 100 percent.”

That PRAP primarily addresses cleanup efforts at Bethpage Community Park—a 12-acre parcel donated to the Town of Oyster Bay in 1962 that presently includes an ice rink, swimming pools and tennis courts. The plan includes the excavation and off-site disposal of park soils, including the removal of hazardous waste levels of PCB, or polychlorinated biphenyl-impacted soils, soil remediation, excavation of the nearby Grumman Access Road, onsite groundwater containment and excavation of impacted adjacent residential yards, as well as addressing soil vapor issues.

For the migrating offsite plume, the agency proposes “at least one groundwater extraction well with necessary treatment.” The plan costs an estimated $81 million.

Additional critics, such as Anthony Sabino, an attorney representing Bethpage Water District and navigating the murky world of the plume since 1980, counter it’s not aggressive enough and that instead of one new well at least six are required. Perhaps no one knows the plume’s costly ramifications or the issue’s overall complexities more intimately than he.

“That’s the wrong approach, certainly for South Farmingdale and Massapequa,” he says of the DEC’s contaminate-first, then-treat wellhead contingency strategy. “Not all of their wells are contaminated. All of our wells down gradient from Grumman are contaminated, so we don’t have that option. We’ve been treating here since 1988.”

Sabino, whose fiery comments at the public input session sparked several moments of resounding applause, tells the Press that to add insult to injury, Bethpage taxpayers have had to foot $21 million in upgrades and treatment processes necessary to remove the toxic contaminants from its drinking water wells, and that the water district will soon be filing a lawsuit against Grumman to force reimbursement.

“We’re mad as hell and we’re not going to take it anymore,” he says.