Phil Franco won’t quit.

Wearing a light blue jacket, a green Seaford baseball cap and holding a sign that reads “Man The Plant,” the 48-year-old father of four is standing at the entrance to Nassau County’s Cedar Creek Park on Merrick Road.

Franco is the co-chair of the watchdog Cedar Creek Health Risk Assessment Committee along with Mark Salerno of Wantagh, who’s standing just a few yards away. They put this rally together to raise awareness about the latest battle in what have been several decades of issues concerning the park’s main resident, the county-run Cedar Creek Water Pollution Control Plant.

About two dozen people have joined them, including Franco’s wife, children and father Vincent, who has been active for decades in safeguarding the public from the plant’s risks. It’s a much smaller turnout than previous rallies at this same spot. Glaringly absent is Legis. Dennis Dunne (R-Levittown), whose district covers the plant, the typically vocal heads of the Wantagh-Seaford Homeowners Association and members of grassroots hell-raisers Green Bay Parkers—all historically outspoken on any matter concerning Cedar Creek or its sister facility, the county’s troubled Bay Park Sewage Treatment Plant.

What Franco and the handful of others are protesting this chilly afternoon in early November, however, couldn’t be any more starved for sunlight or public awareness. They’re part of a growing number of concerned taxpayers and county residents who have caught whispers of a scheme that, if left unchecked, will potentially dictate the future of all county residents’ wallets for the next 40 years.

What Franco and the handful of others are protesting this chilly afternoon in early November, however, couldn’t be any more starved for sunlight or public awareness. They’re part of a growing number of concerned taxpayers and county residents who have caught whispers of a scheme that, if left unchecked, will potentially dictate the future of all county residents’ wallets for the next 40 years.

“This is the worst fight yet,” he tells the Press.

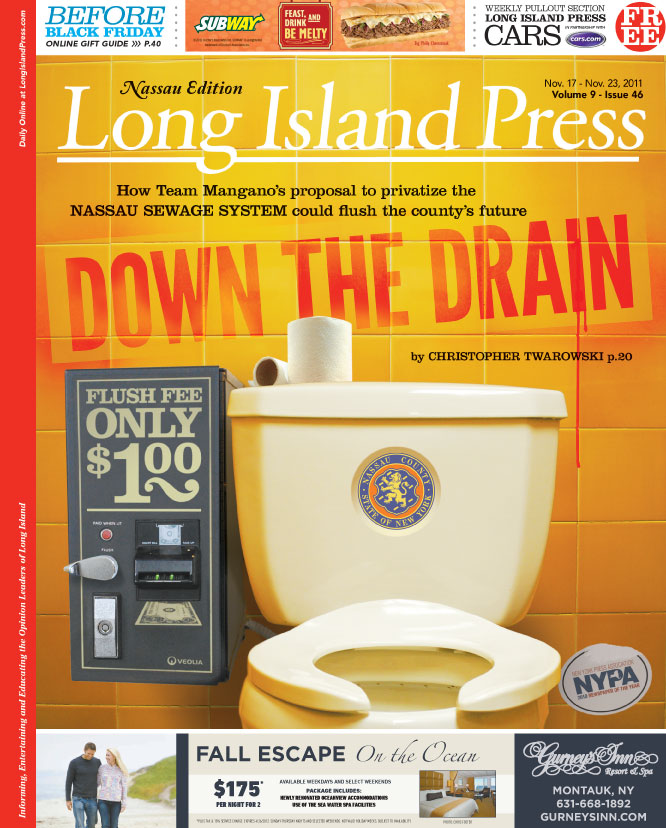

Nassau Republican County Executive Ed Mangano is actively pursuing a plan to sell or lease, either in part or in its entirety, the county’s sewage treatment system—the two aforementioned plants, another in Glen Cove and its vast underground network of pipes and conduits, which currently serves approximately 1 million users—to an unnamed private company. Referred to as a “public-private partnership” or “P3” in his administration’s recently legislature-approved budget and Fiscal 2012-2015 Multi-Year Financial plan—one of the very few publicly available documents containing any mention, however vague, of the deal—proceeds would go toward closing the county’s projected several-hundred-million-dollar budget gaps in 2013, 2014 and 2015. It’s also included as a contingency for 2012.

The county has already hired Wall Street investment giant Morgan Stanley to act as its consultant and advisor through the “complicated transaction,” Mangano tells the Press, with one contract totaling $25,000 and another “going forward for $175,000.”

If successful, he says, the proposal would net between $900 million and $1.3 billion—making it the largest fiscal transaction in Nassau County history.

Short on details to the public, it’s even shorter on the time frame. The budget documents have the operating contract awarded by Dec. 31, 2011, and the selection of a “winning investor” by June 2012. Team Mangano describes the arrangement as a fiscally responsible and environmentally sound means of ridding the county of its “poorly operated” sewage treatment plants—the gross mismanagement and hazardous conditions of which were the subject of an ongoing, award-winning Press investigative series and mini-documentary last year—while generating much-needed revenue and paying down debt.

“Public-private partnerships have proved to provide significant savings for taxpayers, as well as increase efficiencies,” Mangano tells the Press. “In this case, we have the ability to protect the taxpayer, increase efficiencies, protect the environment.

“There’s four companies that have proven the wherewithal to complete such a transaction,” he adds. “And we will soon move to the next step, which is requesting proposals.”

Economists, law experts, environmentalists, watchdogs and a voluminous, easy-to-find, documented track record of similar schemes, however, counter his assessment. They paint a picture of a process tailored to protect the private entities that assume control of the once-public assets, in Nassau’s case something as basic and necessary as sewage and water services, while shortchanging the taxpayers and literally robbing them of their future, among a litany of other negative ramifications—including less transparency, less accountability, more costs for the public and potential public safety and health concerns.

And although the Mangano administration will not publicly release the names of the sewage system’s potential new owners—the county executive tells the Press “I don’t have them myself”—a Press investigation has learned two of the prospective suitors that have been paraded around the sewage plants in recent weeks: U.K.-based Severn Trent and Veolia, the Paris, France-based international conglomerate, whose American headquarters in Illinois recently negotiated (details of which were not released until Nov. 10, seven weeks before the proposed takeover) the $3 million contract to operate Long Island Bus.

“They’re not paying $1 billion for something because they like us,” fires Jerry Laricchiuta, president of Nassau County Civil Service Employees Association (CSEA) Local 830. “They’re paying $1 billion for something because they want to make money. And it’s going to be lots of money… The taxpayers will absolutely see a significant increase in their sewer charges, because we do it for very, very little cost right now. This is not about saving the taxpayers money. This is about Mangano getting his hands on a half a billion dollars cash. That’s it, period.”