Raynham Hall in Oyster Bay (Photo credit: Rashed Mian/Long Island Press)

ANCIENT ART

The rusty blue sign lodged into the freshly manicured grass outside Raynham Hall in Oyster Bay gives subtle clues to counterfeiting’s revolutionary birth.

“Raynham Hall. Built 1740; Used by British As Col. Simcoe’s HDQTS; Information from here lead to Major Andre’s capture after his visits,” it reads. “Home of Robert Townsend Washington’s Spy.”

The former home of Robert Townsend—who was revealed by Long Island historian Morton Pennypacker in the 1930s through handwriting analysis as George Washington’s loyal spy, Samuel Culper Jr.—has been through many changes since the Revolutionary War. Remodeled and decorated with Victorian features by Solomon Townsend in the 1850s, then converted back into a Colonial dwelling when it was deeded to the Town of Oyster Bay in the 1940s, the white two-story with a white picket fence in front breathes colonial wartime stories.

During the revolution, Lt. Col John Graves Simcoe and his Queen’s Rangers occupied the house, and they lived in close quarters with the Townsends for many months.

During the war, Townsend used his access as a merchant and position as a writer for a British newspaper to rub elbows with the loyalists in order to gather information for the Setauket-based Culper Spy Ring, which he did under the constant threat of capture—and death.

“Robert [Townsend] was a good candidate for several reasons,” Claire Bellerjeau of Raynham Hall tells the Press during a tour of the museum. “He was very well-educated, he was smart, he could write well, he could go down to the docks and observe ships, and he knew the names of the ships, he knew the captains, he knew what kind of boat was doing what, he had been involved and surrounded by ships and merchant vessels in that business his entire life.”

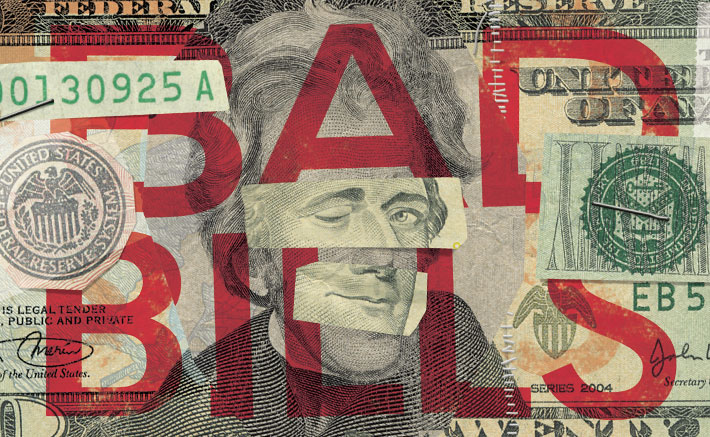

Among his many finds as a spy was a plot to destroy U.S. currency through counterfeiting.

“Townsend hit gold and revived the Ring’s spirits,” writes Alexander Rose in his book Washington’s Spies: The Story of America’s First Spy Ring. “What Townsend had stumbled upon, most likely in his conversation with various officers and officials in Rivington’s coffeehouse, was the British campaign to undermine the American war effort by destroying the Continental Currency.

“New York was the nexus of this counterfeiting trade,” he adds.

The British weren’t the first to use counterfeiting as a weapon of war, but they were well-versed in the craft.

Sign at Raynham Hall in Oyster Bay. (Photo credit: Rashed Mian/Long Island Press)

When the colonies began printing their own paper money—Massachusetts was the first to do so in 1690 to pay for military expeditions—counterfeiting grew rapidly, according to Karl Rhodes’ piece, The Counterfeiting Weapon, in Region Focus, a magazine of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

“It was the proliferation of paper money that begat a new breed of counterfeiters in the New World,” he writes, calling it a “serious problem” by the 1730s. “On the eve of the Revolution, American counterfeiting had surpassed British imperialism as the No. 1 threat to Colonial Currency.”

In 1775, the Continental Congress issued paper currency to help finance the war but it was so easily counterfeited that the money lost value. People would refer to the bills as “not worth a Continental.”

In 1861, the first general circulation of official federal government notes began. Four years later, the Secret Service was created to control counterfeiting because it was “destroying the public’s confidence in the nation’s currency,” according to the U.S. Bureau of Engraving and Printing website.

Over the years, the government has been successful in deterring counterfeiting by changing security features and making the process more strenuous. But criminals evolve, too. And they’re still after money.