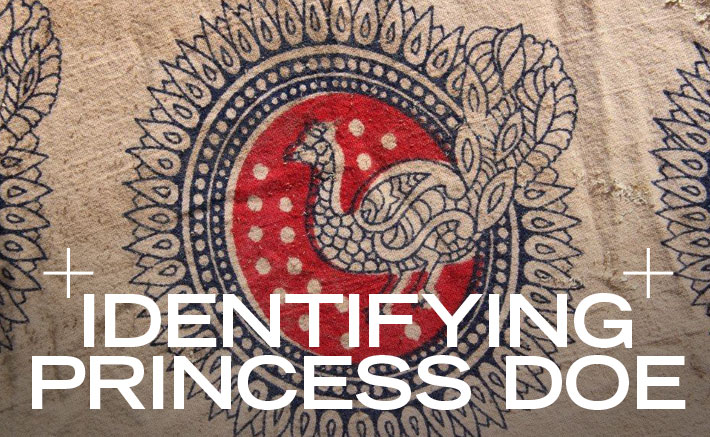

The print bordering the skirt Princess Doe was wearing at the time of her death. (Photo: Warren County Prosecutor’s Office)

In the back of a small roadside cemetery under the arms of a giant maple tree in rural New Jersey she stands, her back toward the steep ravine, the sound of running water below and birds calling back and forth above. Her skirt rustles in the breeze on this warm and sunny summer day. Her T-shirt is stained and torn. Strangers stare at her, taking pictures. She doesn’t say a word.

This headless mannequin dressed in red standing erect among the headstones is an eerie sight from the busy state road that borders the Cedar Ridge Cemetery in this small township of nearly 6,000.

Here, in Blairstown, everyone seems to know each other—police, business owners, neighbors—everyone except for the teenage girl found barefoot, partially clothed and beaten beyond recognition the morning of July 15, 1982.

“She was erased,” says retired Blairstown Police Lt. Eric Kranz, who first responded to the scene. “Her assailant erased her. There was nothing left to her. Whoever did this did it with a vengeance.”

Found with her skull literally smashed into pieces, her face was so violently battered that the medical examiner couldn’t determine her eye color. Today, she is brought back to life, as detectives dress a plastic replica of her body in the original clothes she was wearing the morning a cemetery worker spotted the crucifix tangled in her hair among the dirt and rocks covering the bank, just yards away from where this still-shocked and baffled town buried her 30 years ago. Now more than 100 locals are gathered here for Princess Doe’s grim anniversary.

“We pray for those who are intent on committing acts of violence—may your spirit nudge them and awaken them to realize the value of life,” says Pastor David Harvey from the Blairstown Presbyterian Church, looking down at the pile of flowers left on her headstone. “We pray for the day when her identity may be known, which as of today is known only to you…”

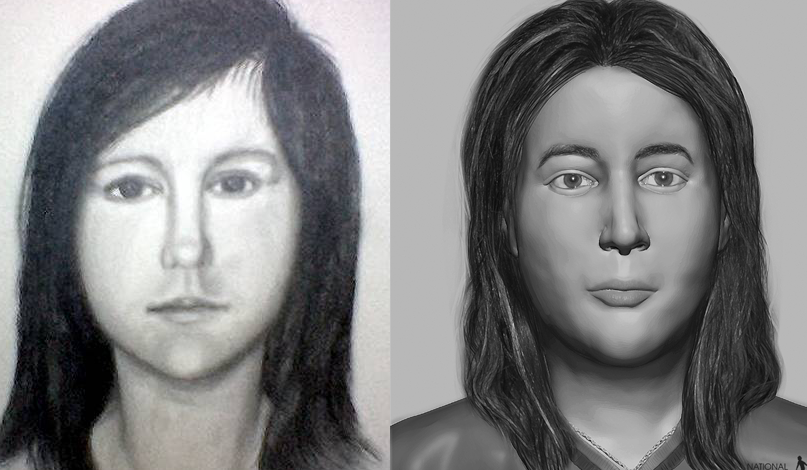

A color-enhanced version of the most recent and most accurate 3D composite of Princess Doe created by the Smithsonian Institute using a CT scan of her skull. (Photo: Warren County Prosecutor’s Office)

It’s a mystery that’s intrigued law enforcement, the media and locals alike. Her story has been the subject of books, TV specials, spurred unidentified and missing persons movements and inspired landmark legislation across the nation—she was the first unidentified crime victim to be entered into the FBI’s National Crime Information Center (NCIC) database. Still, the victim detectives call “Princess Doe” remains a girl without a name.

Technology has advanced rapidly throughout the decades, however, and with the anniversary of her discovery comes the renewed hope that somewhere out there is someone who knows her identity. This July detectives released an updated 3-D composite of Princess Doe and resubmitted DNA evidence for testing. Later this month her story will be featured on America’s Most Wanted.

“There’s an old axiom in investigative work where basically the feeling is that the more the time goes on the less of an opportunity you have to identify somebody,” says Warren County Prosecutor Richard Burke. “We actually feel the opposite in this case.”

And while this cemetery 117 miles from the Nassau County line may seem worlds apart, detectives believe the clues to the identity of their most famous Jane Doe very likely can be found here on Long Island.

The clothing Princess Doe was found wearing on a mannequin that is her approximate height and weight. (Photo: Warren County Prosecutor’s Office)

DEAD AMONG STRANGERS

Her name is made up of more numbers than letters: Depending on what database you look in, Princess Doe is officially known as U-630870962, 1513, 36UFNJ or NJF820715.

She is one of 8,528 documented nameless dead entered by medical examiners and coroners across the country into the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System (NamUs) database, a similar, but not all-inclusive, version of NCIC available to the public.

Those outside of New Jersey might never have heard of Princess Doe at all if it weren’t for the detective who refused to let her be another number in a pool of thousands. Instead of calling her Jane Doe, he nicknamed her Princess Doe. After all, at some point in time, she must have been someone’s little girl.

“I knew this was going to be tough,” says Kranz. “So what I did was I tried to separate her from all the other Jane and John Does and give her a personality of sorts. I got a mannequin and dressed it in her clothes.”

It worked. Most unidentified murder victims don’t make the news after they’re initially found, unless they are later identified, but Princess Doe’s case received nationwide coverage. Still, very little is known about her.

She was white, about 5-feet, 2-inches tall and around 100 pounds at the time of her death, according to the Warren County Medical Examiner’s Office. She was between 14 and 18 years old, had blood type O and four fillings in her back molars.

She still had her appendix and tonsils, and had never given birth. She was found wearing no shoes or underwear. Her ears were pierced, the left one twice, and she had red nail polish only on her right hand. She wore a gold cross, red T-shirt and a broomstick skirt with peacocks printed on the bottom. She had light brown, shoulder-length hair.

No evidence could conclusively determine whether or not Princess Doe was sexually assaulted or had drugs in her system because of the condition of her body, which could have been lying in the cemetery anywhere from a few days to a few weeks, according to the medical examiner’s report.

Longtime Blairstown resident Ann Latimer still remembers the shock of hearing the news. The registered nurse was working the weekend shift at a nearby hospital at the time.

“One of the doctors was reading the newspaper and he said, ‘Oh, isn’t this appropriate: a body was found in the Blairstown cemetery,’” she says. “I didn’t think anything of it. I had gone out to dinner that night after work. I came home and pulled the paper out of the mailbox and right on the front page was the girl’s clothes. I knew it was her.”

Princess Doe’s gravesite on July 15, 2012

On July 13, two days prior to the discovery, at around 11:30 a.m., Latimer was shopping in the local A&P supermarket, which occupied a building, now a tractor supply company, directly across from the Cedar Ridge Cemetery.

“I saw her,” she says, her eyes fixed on the clothed mannequin standing at the foot of Princess Doe’s grave while she recalled the sighting from so long ago. “My daughter was with me. She was 6 years old then, and she said, ‘Oh, mommy, mommy, is that an eagle on her skirt?’ So I said, ‘No, that’s a peacock.’”

Latimer went to the police and they had her hypnotized, hoping to get her to recall more details, such as whether the girl had been with anyone—but Latimer couldn’t.

“I wanted to ask her where she got the skirt because it was so unique, it was pretty,” says Latimer. “But she sort of looked away, and there was a little kid walking past me with one of those little fake plastic shopping carts so that took my attention away, but that was my glimpse of her.”

The most recent, and what is believed to be the most accurate, 3D composite of Princess Doe created by the Smithsonian Institute using a CT scan of her skull. (Photo: Warren County Prosecutor’s Office)

Kranz says after he heard about Latimer’s possible sighting, he went straight to the A&P.

“I checked if there were any cards used, I went through that thing upside-down and checked it,” he says. “I was in every catch basin, in every garbage pail and dumpster—didn’t miss one.”

But it was another dead end. Her fingerprints were checked against millions of others and Kranz reviewed countless missing persons cases, but to no avail.

In order to keep her body from winding up in an anonymous grave in a Potter’s field, residents and local businesses pitched in to provide a gravesite, hearse, casket, flowers and a headstone that reads: “Princess Doe, Missing From Home, Dead Among Strangers, Remembered By All, Born ? – Found July 15, 1982.” Her casket was escorted by patrol cars, and she was buried Jan. 22, 1983 yards away from where she’d been found six months before. More than a decade went by with little movement on the case. Lt. Kranz retired, but stayed with it.

“There hasn’t been a day—not a day—that has gone by where I don’t work on this case. This case created a lot of disconcertion in my life, a lot of issues,” says Kranz. “I went against all the norms—the norms of ‘You know this is one of a million, you always find ’em. Forget about it, let it go. There’s gonna be another one tomorrow’—you know all that thinking, and I just felt that if you applied yourself, that if you just put yourself into this, you’d find her, and the more I did it and the more roadblocks I ran into, the more I dug in.”

Soon all that digging would pay off. Kranz’ successor, Det. Lt. Stephen Speirs of the Warren County Prosecutor’s Office, who took over the case in 1998, was about to get a new lead, one that would take him right to LI’s shores.

The most recent, and what is believed to be the most accurate, 3D composite of Princess Doe created by the Smithsonian Institute using a CT scan of her skull. (Photo: Warren County Prosecutor’s Office)

BUILDING A MYSTERY

The air is just as salty on the other side of the Throgs Neck Bridge in the Bronx as on any of LI’s beaches, but the waterfront property lining Zerega Avenue is a stark contrast to that of its southeastern neighbor. Industrial trucks, buildings, dumpsters and gates block out the rocky slope down to the East River below. From the sidewalks the salty air is the only indication the Long Island Sound is just steps away, but this stretch has a storied and tormented past.

Back in the early ’80s, longtime pimp Arthur Kinlaw—who moved between Central Islip, Greenlawn and Bellport—ran a prostitution ring here in Hunts Point, sending women he would pick up in Suffolk County to sell themselves, said his wife, Donna Kinlaw, in an Oct. 10, 1999 Newsday article. The graduate of Brentwood High School and former employee of the Pilgrim State Psychiatric Center was one of them, she told the newspaper.

In addition to the Hunts Point prostitution business, the couple allegedly traveled the country as far as Alaska, committing all sorts of crimes, from burglary to welfare fraud, each of them accumulating dozens of arrests. In June 1998, Arthur and Donna were arrested in California after Donna allegedly used “Elaina,” the name of one of Arthur’s former Long Island prostitutes, to forge welfare papers, the article recounts. When detectives tracked down the real Elaina, she gave detectives their biggest lead to date in the Princess Doe investigation.

According to the Newsday piece and published reports in other New York metropolitan newspapers, Elaina allegedly told detectives how Arthur, with Donna’s help, drugged, strangled and beat a woman Elaina knew only as “Linda”—a teenager he’d met in a Bay Shore reggae bar called Blackberry Jam, now a church, in April 1984. She reportedly said he’d struck Linda in the head with an aluminum baseball bat on a dark dirt road in Hunts Point when she refused to work as a prostitute for him. He then drove her body to an area near the NYC Department of Sanitation yard on Zerega Avenue, wrapped her in an old shower curtain and dumped her in the East River.

The decomposed body of Linda—who was white, 5-feet, 4-inches tall and about 130 pounds with shoulder-length dark brown hair—washed up weeks later and remains unidentified to this day. Arthur described details of the 1984 slaying in his appearance in Bronx Supreme Court in 2000, according to Newsday, but neither he nor his wife would be connected to the murders of three other women, including Princess Doe, until Donna, in a bid to save herself from life in prison over her part in Linda’s murder, squealed to police.

She reportedly told detectives that in 1983 Arthur beat to death a 300-pound disabled boarder they had taken into their Bellport home to help pay the bills—a black or Hispanic woman in her 20s or 30s who relied on crutches to walk. Donna reportedly told police Arthur dragged the woman out to the backyard of their Michigan Avenue home, where he buried her in a makeshift grave before pouring a cement patio over her. Police found the woman’s remains on Dec. 21, 2000, and she, too, remains unidentified.

Donna also told detectives about Christine Kozma, a drug-addicted Bay Shore woman who turned to prostitution to support her habit, according to the article. Kozma was last seen leaving her East Main Street apartment in September 1982. Her body was later found in a wooded area of Coram with multiple gun shots to her head. Donna reportedly told detectives Arthur had brought Kozma back to their Central Islip home, had sex with her, then killed her when she wouldn’t work the streets for him. It wasn’t the first time he’d done that, she alleged to police.

A recent backyard photo of Arthur and Donna Kinlaw’s former Bellport Home, where the body of a still-unidentified disabled woman–allegedly beaten to death by Arthur Kinlaw during an argument in 1984 and buried under a freshly poured concrete patio soon after–was excavated by police on Dec. 21, 2000.

Donna claimed that in July of that year, Arthur brought home a girl who was about 18 years old, left with her, then came back alone, cleaned out his car and dumped his clothing, according to the Newsday story. Weeks later, during an argument between them, Donna said Arthur admitted to Princess Doe’s murder, reports the article.

“‘He told me if I didn’t go to work, he would do to me what he did to the other girl,’” Newsday quotes Donna as saying. “‘In the middle of the arguing, I said, ‘Well, what did you do to the other girl?’ He said, ‘I’ll take your life just like I took hers.’”

Arthur gave Lt. Speirs some shocking news of his own, the New Jersey detective tells the Press.

“Let’s put it this way, I can’t use the word confession,” says Speirs. “He made some admissions. I’ll put it in these terms: He claimed responsibility for her death. But I have no physical evidence to confirm that, and without the identity of Princess Doe, I have no way of connecting the dots so to speak, putting her in a place where he could have been or would have been at the same time. That’s the unfortunate thing right now. The key thing is to identify her. If we could identify her, then I can try to verify the information [Arthur Kinlaw] provided.”

Arthur also told Speirs something Donna had neglected to mention—that she was in the Blairstown cemetery and witnessed Arthur allegedly beating Princess Doe to death, he tells the Press. When Speirs later confronted her with Arthur’s accusations, the detective says Donna admitted she saw the young girl murdered and helped a forensic artist create a composite sketch of Princess Doe. But was it all true?

“I have no way of disputing it, but I also have no way of confirming it,” says Speirs.

Donna also couldn’t provide a first name for the girl.

“That’s part of the problem,” he continues. “Neither [Arthur] nor [Donna] were able to provide a name, which I felt was quite odd depending on the amount of time they spent with her, if this story is true.”

Arthur was convicted of two counts of second-degree murder. He is currently serving 20 years to life and is eligible for parole in 2018, according to New York State Department of Corrections records. Donna eventually became a witness for the state and pleaded out to 3 to 10 years for manslaughter in Linda’s homicide instead of serving a possible life sentence on murder charges, according to Newsday. She was released in 2003, state records show, but did not respond to a request for comment for this story as of press time.

Left: A composite sketch created by a forensic artist with the help of Donna Kinlaw. Right: A computer-generated image of Princess Doe’s face provided by the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children. (Photos: Warren County Prosecutor’s Office)

Even if the Kinlaw lead comes up blank, Kranz says he still feels strongly that Princess Doe is from LI.

“[The Kinlaws] are one reason. That’s not the whole reason,” he says. “You can call that ‘detective’s hunch’ or whatever the case may be, but we just seem to be always going out towards that area.”

For now, the murder of Princess Doe remains a mystery but Speirs follows every tip.

“There are other theories, but again, I can’t base my facts on theories, I have to base my theories on facts,” says Speirs. “And I have really no strong facts that appear to say the Kinlaws are involved or not involved. It’s an open door and there have been other persons of interest prior to that, and there have been persons of interest since then. Again, I go back to that unfortunately we have no way of substantiating any of this information because no one is providing a name or identity—we don’t know who she is. At this point, there is no physical evidence to tie any of these people in to this crime.”

All of this could soon change, however.

Retired Blairstown Police Lieutenant Eric Kranz

DOWN TO A SCIENCE

In 1999, Speirs had Princess Doe’s body exhumed to retrieve DNA from her remains to help in the identification process. Back then, DNA analysis was in its infancy, but the technology has come a long way over the past decade and samples taken in the past could provide new clues today.

“Preliminary results from those tests suggest that we may have some trace evidence that does not belong or was not contributed by Princess Doe,” says Speirs. “Now, we can resubmit [the DNA] because we can do so many better things now. It’s more advanced so we can take the smallest amounts of trace evidence and be able to develop a DNA profile.”

That means detectives might be in possession of DNA belonging to Princess Doe’s killer, or at the very least, someone who was with her before she died who could possibly identify her.

“If this evidence does prove to be contributed not from Princess Doe, but from someone other than Princess Doe, then that clearly gives us a person of interest,” says Speirs. “I’ve never been more optimistic than I am now, and I’ve been around the block on everything you can imagine, all over the place, with this case.”

Det. Lieutenant Stephen Speirs of the Warren County Prosecutor’s Office

Speirs resubmitted the DNA in July, and the results are due back from the lab in September, along with other test results. Princess Doe’s hair is also undergoing analysis in an attempt to see what part of the country she was in prior to her death.

“The scientists, hopefully through metal deposits in her hair, will be able to focus us a little bit more in the areas where she may have been or lived,” says Prosecutor Burke. “The passage of time has really helped us with regards to technology and forensic science.”

And there’s a lot riding on that science.

“If [the tests] show she was from the East Coast and the metropolitan area, that’s beautiful. That’s one more thing closer to matching the story with the Kinlaws,” says Speirs. “If it says she’s from the Midwest, then that kind of throws things out a little bit. But it doesn’t completely eliminate it because she could have been from the Midwest, and came here and stayed here for a period of time. Who knows?”

And finally there’s the new composite released just weeks ago, created by the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D.C. using a CT scan of Princess Doe’s skull, which may be the best hope yet.

“All of the other renditions prior to this were renditions by artists, and each one of them have their own personality in that,” says Kranz. “Through their experience they say this eye is lower as a rule or this nose is moved, this nostril is wider—they each had their own conception of what she could have looked like. What Smithsonian did in this case was take all that emotion out of it and use pure science. So this is 100 percent unadulterated science, and what makes me feel that this is the closest rendition to what she looks like that’s ever been done.”

There is also still the possibility that someone will recognize Princess Doe’s clothes. Although the label was missing on the shirt and the label on the skirt was faded, Speirs says he found a company in the Midwest that manufactured the exact type of skirt she was wearing back in the ’80s.

“They sent them all over the place including the metropolitan area, so that could fit,” he says. “It could have been purchased somewhere in the Long Island area or Manhattan.”

Though officially retiring this week, Speirs, just like Kranz, tells the Press he will never abandon Princess Doe’s case.

“I still live locally,” he says. “I’m really not going anywhere; I will still be part of the case.”

So will Prosecutor Burke.

Left: A sketch created by a forensic artist using details provided by Donna Kinlaw. Right: The most recent, and most accurate according to detectives, digital composite created from a CT scan of Princess Doe’s skull

“We really feel that at this point in time we need to focus on the identity of this young woman, that’s our goal,” says Burke. “We also believe that by doing so not only will we bring closure to Princess Doe and her family but hopefully be able to identify the person who committed this horrendous act.”

For Kranz, the quest to identify Princess Doe has become personal.

“I had experienced the loss of my daughter Michelle in 2007 from cancer,” he says. “Through the course of her illness, Michelle and I spoke many times of the Princess Doe case and what it meant to us.

“Through the process of [Michelle’s] passing, I thought about how we were able to talk about things,” he continues. “I held her hand, I kissed her and hugged her and held her body. We shared a gift, a God-given gift, one I will never forget. There are a whole bunch of families out there, thousands upon thousands, that will never have what I had, never be able to say goodbye…

“One of the reasons why I’ve stuck with this as long as I have…I think it’s a matter of value, I really do. And I think we have become very coarse. I mean it sounds odd from a cop.

“I’ve seen death,” he adds. “I’ve seen more death than I care to ever see again. But I just think that if you lose that disgust over somebody that young being murdered, if you lose the despair over it, I think we’re a doomed society.”

If you have any information that could be related to Princess Doe, please call the Warren County Prosecutor’s Office Princess Doe Tip Line at 1-866-942-6467.

PRINCESS DOE UPDATE (SEPT. 24, 2012): Princess Doe Likely From Arizona, Spent Time on Long Island

GIRLS DISAPPEARING: BEHIND THE HEADLINES OF THE LONG ISLAND SERIAL KILLER CASE