Dale Paetruska spots a pleasure craft packed with 20-somethings zipping through yacht-clogged Sag Harbor and flicks on the blue lights and sirens of his 27-foot Boston Whaler.

“Let’s go say, ‘Hello,’” he tells his partner, Jeff Louchheim, as the two chase down the young party boaters.

Paetruska, a mustached, navy-blue clad seadog of an East Hampton Town Bay Constable, conducts a quick interview over his boat’s side rail before jumping back to the helm to avoid drifting into a catamaran—one of the hazards that come with working on the water is that everything is constantly moving. His team quickly finds a new spot to restart their probe.

“Oh my god, look at how safe we are, guys,” one young woman sarcastically says after her group proves they have enough lifejackets.

The constables blow it off. The skiff appears overcapacity, though it lacks an onboard capacity plate, which would state how many people are legally allowed on board. Without it, Paetruska and his partner don’t have the proof they need to issue the $75 fine for having too many people on the vessel. He lets them off with a warning instead.

Some boaters view him as a fun-seeking torpedo, blowing up nautical parties with pop quizzes about boating safety. Yet Paetruska just wants to make sure everyone gets home in one piece.

“It starts out as a day of fun,” he says—ironically on a day when Southampton police divers were simultaneously searching for a 26-year-old drowning victim four miles away in a Noyack pond. “People shouldn’t go out for a day on the water and come home in a body bag.”

After 18 years of patrolling the Hamptons’ waters as a bay constable—prior to his current position, for Southampton—Paetruska’s seen a lot. As he slowly cruises on patrol around the mooring field at sunset, he recalls some of the worst: The man whose daughter was fatally struck by the propeller after she was sitting with her legs over the bow of their boat and fell off when they hit a wave. The young couple on a personal watercraft, or PWC—such as Kawasaki’s popular Jet Ski—who drowned after it ran out of gas, stranding them at night. The father whose 12-year-old son was hit and killed by a novice boater while he was jumping wakes on a PWC a week before his birthday.

As he speaks, Paetruska joins forces with the Sag Harbor village harbormaster just over the town line in Southampton alongside other marine units from nearby Shelter Island, Southold, U.S. Coast Guard—even Suffolk County deputy sheriffs—who fan throughout the bay to prevent future tragedies in the crush of boaters anchored for a pre-July 4 fireworks show. Rookie night-boating collisions are expected. Their top priority is busting drunken boaters, especially after an alleged Boating While Intoxicated (BWI) death on the Great South Bay a week earlier.

It’s been a long day for Paetruska that started at 6 a.m. This evening assignment follows his morning partnered with Customs and Border Patrol agents, checking foreign-flag vessels for passports and ensuring they notify authorities upon reaching Long Island ports, a federal rule not all are aware of, same as many state boating laws. Some of the inspected yachts hail from Canada, the Cayman Islands and the Bahamas—part of a four-year-old sporadic effort dubbed Operation SHIELD (or Operation Gateway, as it’s known in Nassau).

Besides enforcing local, boating, fishing, hunting and environmental laws—as well as search and rescue missions—New York State and federal authorities increasing rely on these peace officers for critical intelligence from the 1,000 miles of Long Island coastline they jointly protect. Some assignments, such as cracking down on errant jet skiers, seem too modern for the original job description of a bay constable—a title that dates to colonial days, when many LI towns were established. But these officers also draw inspiration from relative recent history, like the Coast Guardsman who caught Nazi German spies sneaking ashore in Amagansett during World War II.

Paetruska, a former president of the New York State Harbormaster and Bay Constable Association, juggles his duties with a deep-rooted love of the job despite the added pressures that come from seeing his unit’s personnel and budget slashed. He’s not alone in the sentiment. The job is fraught with many of the same perils as full-fledged police officers on land. There’s also the added obstacle of boaters’ fatigue from the wind, sun, saltwater spray and constant rocking of the boat—not to mention longer response times.

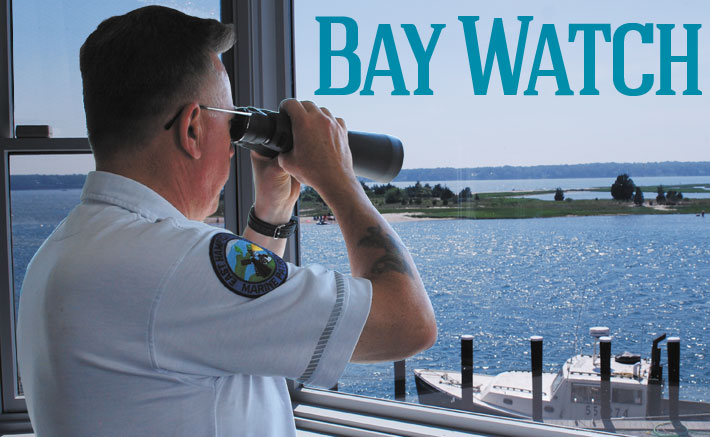

“We’re it, we’re the ambulance, we’re the fire department,” says Ed Michaels, East Hampton town’s chief harbormaster, a retired Montauk-based Coast Guard master chief, and chair of the Eastern LI Maritime Law Enforcement Task Force, comprised of the five East End townships outside the Suffolk County police Marine Bureau patrol area.

“It’s an unforgiving environment,” he says while looking out over Three Mile Harbor in the constables’ outpost bordering Gardiners Bay. “We’re all in the same boat.”

That environment may get a whole lot more unforgiving for bay constables monitoring Nassau’s waters if recently threatened cuts to the county’s workforce by Nassau County Executive Ed Mangano affect its police department’s marine bureau, which would potentially force the county’s three towns top pick up the slack. Those additional law enforcement duties would fall upon two townships whose constables aren’t even armed. All while the Town of Oyster Bay’s marine unit boss is currently under criminal investigation.

“We live on an island, we’re not getting rid of our Marine Bureau,” Mangano told reporters in April 2011, when such concerns first surfaced.

“To even consider having another jurisdiction perform those duties would be a disservice to not only the people of Nassau County who use the waterways for pleasure, but also for the people that use the water as a place of business, like the baymen,” says James Carver, president of the Nassau County Police Benevolent Association, the union that represents rank-and-file officers.

Despite the assurances, some bay constables, who wish to remain anonymous since they are currently on the job and fear retaliation, tell the Press such potential cuts are still very much a concern.