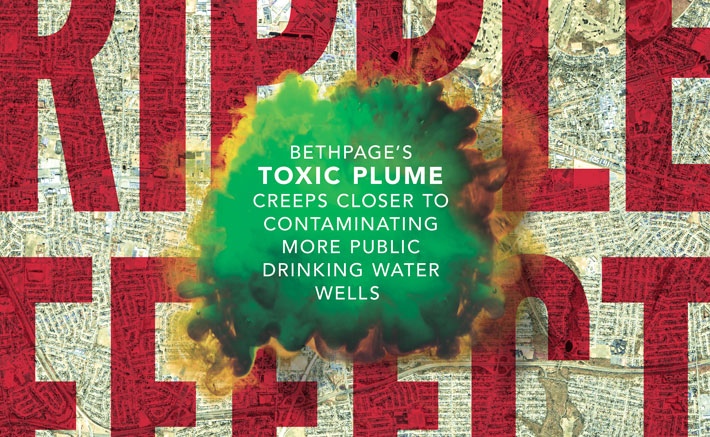

“What we want is the Navy and Grumman to stop the plume… Why are we letting a perfectly good water supply get contaminated when it can be stopped.” – Massapequa Water District Commissioner John Caruso

INDISPUTABLE

Few can argue the historical, societal and geopolitical significance of Grumman, now Northrop-Grumman, and the role the defense manufacturer has played in not only shaping the future of the United States, but in sculpting the future of the entire world.

Grumman was instrumental in helping the Allies win World War II through its development of cutting-edge technology and aeronautical designs in military aircraft and weapons systems. That legacy continued throughout the decades. It developed and manufactured the F4F Wildcat, the F6F Hellcat and the F-14 Tomcat, among other fighter planes. It manufactured satellites for NASA. Grumman helped put man on the moon as the chief contractor for the Apollo Lunar Module. In its heyday, the company was the largest employer on Long Island, thus helping found the nation’s first suburb by creating jobs for tens of thousands of Long Islanders after WWII, when many returning veterans decided to call the Island home.

According to DEC documents, the 600-acre Grumman Aerospace complex included both Grumman-owned and operated plants and government-owned and contractor-operated plants. Grumman’s operations began in 1930 and the NWIRP started operations in 1933. All manufacturing ceased at both facilities in 1996, they state, and the complex was listed in the Registry of Inactive Hazardous Waste Disposal Sites in New York in 1983.

In the eyes of the agency, the complex is divided into three operable units, or as the DEC defines them: “a portion of a remedial program for a site that for technical or administrative reasons can be addressed separately to investigate, eliminate or mitigate a release, threat of release or exposure pathway resulting from the site contamination.”

The site’s former manufacturing plant area is designated Operable Unit 1 (OU1). Operable Unit 2 (OU2), DEC records show, consists of the groundwater contamination plume and is designated as a joint operable unit for both the Grumman and NWIRP sites. Operable Unit 3 (OU3)—whose Proposed Remedial Action Plan, or PRAP, was the subject of the June 12 public meeting at Bethpage High School—consists of the former Grumman settling ponds, the Grumman Access Road, some adjacent property and impacted groundwater not addressed by OU2.

It’s tough to pin down exactly when the first red flags were raised regarding practices at the facilities that would eventually contribute to the current environmental dilemma now threatening so many communities’ drinking water wells—after all, the EPA didn’t come into existence until 1970, the Clean Water Act 1972 and Safe Drinking Water Act, which sets public drinking water supply quality standards, wasn’t until 1974—but voluminous state DEC records indicate a long history of environmental unfriendliness at the complex.

“From 1943 to 1949, Grumman disposed of chromic acid wastes directly on the ground or in open seepage basins,” reads OU2’s 2001 report.

“From the early 1950s to 1978, drums containing liquid wastes were stored on a cinder covered area over a cesspool leach field,” it continues. “This leach field may have been used to discharge process wastewater.”

“Prior to 1984, some Plant 3 production-line rinse waters were discharged in the three on-site recharge basins. These waters were directly exposed to chemicals used in the industrial processes (rinsing of manufactured parts),” it adds.

“The primary groundwater contaminants are chlorinated VOCs [Volatile Organic Compounds], which were either used and disposed of at the sites or are breakdown products of these chemicals,” it concludes. “These compounds are: perchloroethene (PCE); trichloroethene (TCE); dichloroethenes (DCE); vinyl chloride; 1, 1, 1-trichloroethane. Inorganic analytes (metals), specifically arsenic, cadmium and chromium were detected in groundwater samples that were collected at the sites.”

Increased PCE, TCE and DCE exposure can have detrimental effects on the central nervous system, blood, brain, bladder, kidney, liver and reproductive organs, according to the NYS Department of Health.

There were “settling ponds” located on the site, which from 1949 till 1962 states the OU3 PRAP, was used for “the dewatering of sludge, including neutralized chromic acid waste.” Those ponds, currently buried beneath baseball fields at Bethpage Community Park, contain chromium and PCB-impacted fill materials. A former “Rag Pit Disposal Area” contains chlorinated and non-chlorinated VOCs, it reads. The Grumman Access Road, within earshot of children frolicking in the park’s swimming pools and abutting residential homes, is “impacted with PCBs, chromium, and to a lesser extent, cadmium,” the report continues.

“The OU 3 investigation found significant soil, soil vapor, and groundwater contamination at the site,” it states. “Contaminants of concern”—hazardous wastes sufficiently present in frequency and concentration in the environment to require evaluation for remedial action—include: Trichloroethylene; 1,1,1 Trichloroethane; aviation engine oil; chrome etchant; machine oil; paint; paint solvents, Polychlorinated Biphenyl oil; Tetrachloroethene; Toluene; Chlorodifluoromethane; Dichlorodifluoromethane; Chromium; Cadmium; Arsenic; and Freon 113.

Yet despite the ever-expanding toxic cocktail headed their way, the importance of Grumman and the Navy’s work is not lost on any of the plume’s critics, nor the hundreds who packed Bethpage High School to hear the DEC’s latest plans on dealing with their mess. They just want it cleaned up, now.

“They built 330 F6 Hellcats per month,” boomed Bill Ellinger, a lifelong Bethpage resident and commissioner at its water district, at the public meeting. “They used to go right over my house when they tested them.”

“They had equipment that you couldn’t fit in this room that was being lubricated by all the stuff that they dumped overboard by the ton,” he said. “Now it formed this tremendous plume that the DEC knew about in 1969, when the waters all went bad and they called us, the Bethpage Water District… That’s 35 years ago! And they’re still doing studies!? Are you guys kidding me or what?

Caruso, the Massapequa water commissioner, tries to stay positive.

“Let’s face it, without Grumman and the Navy doing what they did in World War Two, we might be speaking a different language today,” he says. “Now let’s use all of that technical horsepower and clean this up, which shouldn’t be much of a challenge.”

A Northrop-Grumman spokeswoman tells the Press in an emailed statement the company “has been actively engaged in environmental and remediation activities at the complex for over 20 years, during which time the company has invested over $105 million.”

“The Navy is in the process of compiling and updating the costs of the extensive investigation and cleanup work that it has undertaken for NWIRP OU-1 and OU-2 and it is therefore not in a position to provide a cost figure at this time,” writes a Navy spokesman in an emailed response to questions for this story.

Massapequa residents need look no further than the dead-end block of Sophia Street in Bethpage to see the future, because Caruso’s worst fear is Bethpage’s reality.