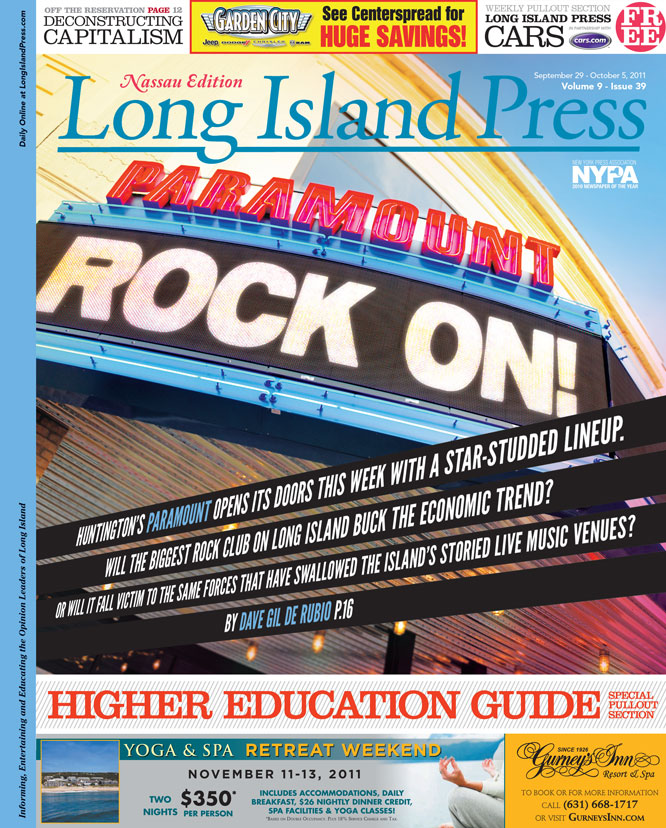

On paper, The Paramount appears to have a number of factors aligned to ensure ongoing success: Live Nation-fed booking, a multi-million dollar facelift and an experienced music industry veteran heavily involved in the decision-making. But the closing of the Crazy Donkey the week prior to The Paramount’s launch is a reminder of a Long Island live music landscape haunted by the ghosts of numerous storied venues.

Dating back to the 1960s and spanning through the ’70s, ’80s and ’90s, Long Island has been a rich market for live music venues—clubs such Hempstead’s Calderone, Island Park’s The Action House, Islip’s Hammerheads, Plainview’s Vanderbilt and Massapequa’s Solomon Grundy’s, to name just a few that have come and gone. The Grateful Dead, Aerosmith, Patti Smith, Social Distortion, Twisted Sister and Living Colour are just a few of the myriad national and local acts that played LI stages on their road to fame.

Arguably one of the Island’s most legendary spaces was My Father’s Place. Founded by Michael “Eppy” Epstein in 1971, the Roslyn rock club played host to more than 3,000 artists until it closed in 1989. Among the artists who rocked this 500- to 600-seat space were The Police, Billy Joel, Bruce Springsteen, The Ramones, Runaways, Lou Reed and countless others. The legacy left behind by the club led to the book Fun and Dangerous: Untold Tales, Unseen Photos, Unearthed Music from My Father’s Place and earned it the honor of being the first venue inducted into the Long Island Music Hall of Fame last year.

Epstein’s indefatigable skills as a developer of talent found him also booking bands like Ministry and OMD at Farmingdale’s Spyz from 1984 through 1986 and working closely with WLIR/WDRE [a radio station later owned by Press parent company, The Morey Organization], going so far as to have live shows broadcast from My Father’s Place on Tuesday nights.

“The club ran from 1971 to 1989 and with radio stations like WLIR/WDRE, there were records being played and sold on Long Island to the point that WLIR became the ninth largest market in the United States for the sale of record product,” Eppy tells the Press. “So that made it so that an artist had to stop on Long Island.

“We had per capita more bands that made it than any other suburb in the world because of the radio that we had here,” he continues. “Long Island was always a great place to play.

“I stayed open every night of the week for ten years. If I had a night that was open, I’d fill it with local bands. Not cover bands. I didn’t do cover bands,” he adds. “As a matter of fact, you couldn’t play my club if you were a cover band and that was because I was looking to develop new singer-songwriters because record companies at that time were always looking hungrily for new talent and that’s what it was all about.”

The 1980s proved to be a fertile time for live music on LI. The aforementioned radio station also had a relationship with Lido Beach’s Malibu and Levittown’s Spit. The former got its start in 1980, and with the help of its radio partner, became an outpost for new wave music through the 1980s up until it closed in the mid-1990s. Aside from hosting a number of dance nights centered around LIR’s “Shriek/Screamer-of-the-Week,” Malibu was also the site of shows by The Ramones, Squeeze, Pixies, Blondie and one of the first American performances by U2.

Founded in 1983, Spit was another New Wave oasis during certain nights of the week, playing host to a number of upcoming artists including Duran Duran, Billy Idol and Flock of Seagulls until the club shut down in 1989. Spit was a part-time operation, sharing the space with Uncle Sam’s, a disco founded in 1979 where a then-unknown Madonna performed in 1983.

One of the scene’s greater unsung heroes was Frank Cariola, an ex-songwriter/Four Seasons road manager who founded Bay Shore’s Roxy Music Hall in 1978, later changing its name to The Paramount and eventually, Sundance. The latter became synonymous as a bastion of hard rock/heavy metal acts throughout the 1980s. Dream Theater played its first concert here. Cinderella and Poison had early gigs at Sundance. Saxon, Megadeth, the Red Hot Chili Peppers, Slayer—the list goes on and on and on. Guns N’ Roses also played it in the beginning of their career.

“I had ’em all,” says Cariola. “I was the only one because I enjoyed what I was doing. I brought in the acts that I believed in and I took chances, like when I booked Axl Rose and Guns N’ Roses.

“That was 1987,” he adds. “They were a brand-new group that came from California and I was the first gig. I bought them without even knowing who they were. I guessed right.”

Sundance’s first two incarnations were as a country/western venue and a stop for oldies acts. So before Axl Rose or Anthony Kiedis shook their skinny butts in Bay Shore, the Sundance stage played host to George Jones, Roy Clark, Roy Orbison, Bo Diddley and Ricky Nelson, among others. Cariola closed shop at Sundance in 1991 after Southside Hospital bought the property, moving his base of operations to Huntington, where he re-opened The Roxy. Its slate of performers was equally impressive—Korn, King Diamond, Biohazard, Life of Agony and Marilyn Manson, among many others—before it closed in 1996.

By the late 1990s/early 2000s an emerging emo scene benefitted from the opening of two clubs, The Downtown and The Crazy Donkey. Both located in Farmingdale, the former started out as a sports bar before owner Dave Glicker and some partners began hosting live music shows here in 2001.

With the club’s motto, “It’s about the music,” The Downtown and its capacity of 450 was where Taking Back Sunday, Glassjaw and Straylight Run played early on, as well as smaller local acts Lux Courageous, As Tall as Lions and Bayside. The Donkey was founded a year later by disco impresario Gus Semertgis, Jr., and a group of partners, and while there was competition with The Downtown up until it closed in 2005, the surviving nightclub picked up where its defunct peer left off. A mix of emo (Saves the Day), hip-hop (KRS-One), death metal (Suffocation), alt-rock (Built to Spill) and even the occasional pop act (Demi Lovato) could be seen during the nine years that the club existed.

Then there’s the IMAC, the 550-seat nonprofit founded in 1973 by the late Michael Rothbard and his partner Kathie Bodily. Up until it closed in 2009, IMAC was where fans of jazz, folk, blues and other more niche genres came to see artists, like Joan Armatrading, David Bromberg, Spyro Gyra, Buckwheat Zydeco, Phoebe Snow and Bob James.

All this is the weighty legacy of live music The Paramount stands to inherit and hopefully further.

“They’re living my dream and I wasn’t just doing all this for the money, I was running clubs because it was my dream,” Cariola says of Doyle and the new Paramount. “I’m glad that somebody had the chutzpah to do it and to do it right.”

Longtime Long Island music booker Christian McKnight—who helped spearhead the rise of emo from the Island’s incubator venues to the world stage and now works for corporate giant Live Nation—says The Paramount, with its much larger capacity, fills a missing piece of the Island’s live music puzzle, filling the hole between its smaller clubs and much larger spots, the Jones Beach Amphitheater and Nassau Veterans Memorial Coliseum.

“There was a big gap between the Donkey and anything bigger,” he explains. “The problem is that you literally don’t have a place for a band to play after they play the 850 at the [now closed] Crazy Donkey, and when you’re talking about bands like Brand New, Taking Back Sunday, Dashboard Confessional or Glassjaw—these bands that can sell a substantial amount more tickets but don’t want to play arenas—you really don’t have a place for them to play.

“The Paramount is a great venue in a great location and is something that Long Island has been missing for a very long time,” he continues. “As you can tell from the calendar, we have arena-sized bands playing in that room.

It’s pretty amazing that we have the caliber of bands that we have and I think that it’s because there’s been that void of a real venue on Long Island for a real long time.

“Long Island is a fantastic market,” says McKnight. “There are a lot of people out here. There are a lot of concertgoers and people that travel to New York City. So now people have the opportunity to see a great show on Long Island.

“It’s something that Long Island desperately needed,” he adds. “It is a great bridge.”