Few were surprised that George Guldi, the ex-Suffolk County legislator convicted of insurance fraud and grand larceny earlier this year, decided to plead guilty late last month for his role in an $82-million mortgage fraud scam, which left a “trail of financial ruin heretofore unseen in this county,” according to District Attorney Thomas Spota.

Guldi, a Democrat, committed these crimes when he was no longer a lawmaker, but some say his behavior adds to the impression that a dark cloud overhangs the political landscape, casting a long shadow over the ethics of those the public elects to serve. The unprecedented action of County Executive Steve Levy, turning over his $4.1 million campaign war chest to Spota in March and agreeing not to run for re-election this year because “questions have been raised concerning fundraising through my political campaign,” did nothing to dispel that cloud.

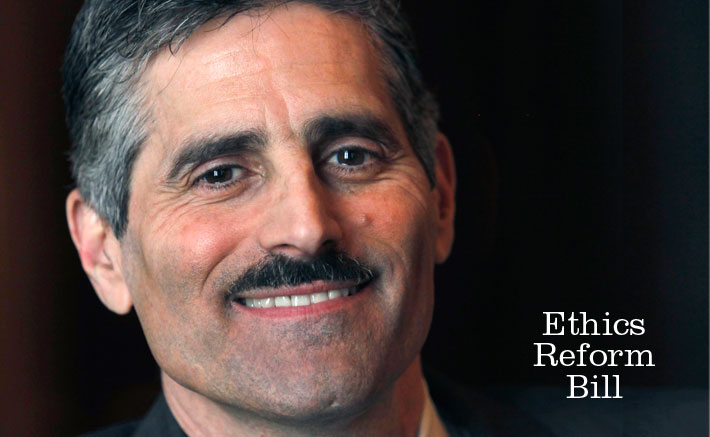

But two bipartisan bills proposed last week in the county legislature would go a lot further to shed much-needed light on the backgrounds of public servants. If passed, possibly as early as next month, they would set up the toughest ethics code and compliance procedure in New York State. Ironically, having a new ethics board in place could be Levy’s, and by extension Guldi’s, lasting contribution to Long Island.

“Ethics legislation has a tendency to let sunshine in,” says Legis. Bill Lindsay (D-Holbrook), the presiding officer. “Our citizens will have the ability to know what their elected officials and their appointed officials are doing and how they make their money because it will all be online,” Lindsay tells the Press, adding that the new “crystal clear” ethics rules would also pertain to the officials’ spouses.

Watching a former legislator like Guldi fall from grace is “not a happy day for anybody who holds public office,” Lindsay adds, “but it’s another reason the ethics code should be the strictest as we’re proposing.”

THE COMPANY WE KEEP

Those familiar with the facts of Guldi’s second case, which involved more than 60 properties mostly in the Hamptons, expected the guilty verdict, but Guldi’s timing may have caught them off guard. The ex-politician, who served in the county legislature from 1994 to 2003, admitted to 34 counts of grand larceny and one charge of scheme to defraud, when he threw in the towel just as the jury was being picked. Perhaps local observers were hoping that this “circus,” as some called the first month-long trial, would continue because Guldi, a flamboyant figure, was representing himself, and that episode was especially engrossing, particularly his thwarted efforts to drag Levy, his former friend and business partner, into the proceedings.

But many were shocked by the one-to-three-year sentence that Judge James F. X. Doyle promised Guldi, since he was already serving four to 12 years for pocketing $853,000 in the previous insurance fraud case. Doyle said Guldi could serve the sentences concurrently, which Spota called “completely inadequate.” Guldi’s formal sentencing is set for Aug. 31; afterwards he’ll leave LI for a while to serve time at an upstate correctional facility.

His treatment at Suffolk County jail hasn’t been too shabby, Guldi’s son Edward tells the Press. “He’s good,” says his son about his dad. “He’s lost almost 50 pounds and his diabetes is much better. His health is improving.”

With his plea, Guldi follows his co-defendant Brandon Lisi, who also pled guilty on July 29, and another co-defendant Ethan Ellner, who pleaded guilty in 2009 and had become a cooperating witness for the DA.

Ellner and Guldi had been arrested in 2009 in the $82 million mortgage fraud case, which linked real estate scams in the Hamptons to S&M dominatrices in SoHo. Ellner was also linked to Levy. They’d pumped iron together and reportedly shared a house. Levy was an usher at Ellner’s wedding. The county executive also gave a company owned by Ellner, a convicted felon, $85,000 in county title work.

“I just tried to give a guy a second chance in life,” Levy told Newsday when the story broke.

At his first trial, Guldi tried hard to implicate the county executive, claiming that Ellner had told him that he’d had to pay a bribe to Levy to get county work. But Spota had Levy’s name redacted from court documents and resisted Guldi’s efforts to force his former political ally to appear. After all, the trial had nothing to do with Levy.

Yet this winter when Spota and Levy announced that the county executive would fork over his war chest—which won’t be dispersed until after November’s election—Guldi was in high dudgeon, complaining that Levy had apparently bought himself “a get-out-of-jail card” for $4.1 million. In a court filing, Guldi wrote that “Levy’s obvious cozy relationship with Spota…” is “…reflected in the secret deal, which on its face violates the Election Law of the State of New York, and the spirit if not the letter of the Constitution.”

Spota’s office would not comment on this accusation. Back in March, when the agreement was announced, Spota said, “I am confident that Mr. Levy did not personally profit.”

But the devil’s in the details, as they say, and no details about this agreement have been released, irking Legis. Ricardo Montano (D-Central Islip), a former federal civil rights attorney now in private practice, who’s repeatedly clashed with Levy over the years.

“We have a right to know what other appointed and or elected officials were involved,” Montano says. “Whatever Levy did, he did not do alone!”

Levy’s former chief deputy, Paul Sabatino, who also served as the legislature’s general counsel for almost two decades, expressed his admiration for the deal Spota worked out with the county executive because it avoided a long and costly trial.

“From the standpoint of neutralizing a guy and rendering him politically impotent and destroying all of his moral authority, in that respect I think it was brilliant,” says Sabatino, who’s had a very public falling out with his former boss, no doubt exacerbated by Levy’s aides lodging an ethics complaint against him in 2008 for his work on behalf of the Foley Nursing Home—a complaint that went nowhere—as Levy was fighting to close the facility. [Just last week the Suffolk legislature voted to extend funding of the nursing facility through the end of the year.]

Levy’s political trajectory was set on a downward course, many observers say, last summer, when Newsday reported that the county executive had not been filing the county’s disclosure form. Instead he’d been using the less extensive state form. Levy explained that he was entitled to be an exception to the county’s rule because of his role on the State Pine Barrens commission, which the Suffolk Ethics Commission found acceptable even though it didn’t jibe with an Appellate ruling in 2003 to the contrary.

Soon thereafter, revelations surfaced about Levy’s campaign contributors and the profitable work that a transcription company run by his wife, Colleen West, was doing with county vendors. The ethics commission had said that she could continue to do business with the vendors as long as she didn’t identify herself as Levy’s wife.

AND JUSTICE FOR ALL…

Spota may have shelved Levy’s campaign war chest, but he’s still looking into the administration, his spokesman confirms. The district attorney’s government corruption bureau has an ongoing investigation of the Ethics Commission, which one county legislator said Levy had turned from “a shield into a sword.”

“Time will tell that the county executive exerted considerable influence on the ethics commission,” says Joseph Sawicki Jr., the county comptroller. Last August, Sawicki, a Republican, wrote Spota to complain that Levy was apparently releasing the financial disclosure statements that, as the comptroller, he’d had to file with the Ethics Commission, and that Levy “is using them for political and other extortion-type purposes.” Levy’s office has denied this allegation.

Legislators like Montano found it galling that the Ethics Commission seemed to have one standard for Legis. Ed Romaine (R-Center Moriches), which supposedly prevented him from casting key votes on funding the Foley Nursing Home because his wife and sister-in-law worked there, and another for Legis. Lou D’Amaro (D-North Babylon), who is married to Christine Malafi, the county attorney, whose duties entail defending the county executive.

Explains Montano, “If I walked into court and the DA is married to the judge, I know I am in trouble. I look at my client and say, ‘You’re in deep shit!’”

For several years Montano had tried to pry the Ethics Commission loose from the county attorney’s office but to no avail. It didn’t help that his own caucus saw him “as a pariah,” as he put it, for clashing with Levy when Levy was still a Democrat (he became a Republican in 2010). Montano finally got the legislature to pass a budget line so the commission could hire an outside counsel. It backfired, Presiding Officer Lindsay says, “because they took the $80,000 we appropriated … and used it to fight the investigation.” Under Lindsay’s prodding, the legislature had set up a special committee to look into the Ethics Commission, which did not sit well with Levy.

“They were issuing press releases every day knocking the investigation,” says Lindsay.

But the new board promises a clean sweep. It would have five members, not three, and occupy an office not under the county attorney’s wing, nor be tied to the legislature. It would have its own outside counsel. Coupled with the board’s creation is an expanded ethics code, which would resolve once and for all any uncertainty about who should file a county financial disclosure form.

“At its heart, conflict of interest means having divided loyalty toward the people you represent,” says Russ Haven, staff attorney with the New York Public Interest Research Group, a nonprofit watchdog dedicated to good government. “In that respect it’s very simple. In practice it can be trickier, but if you have an agency that’s enforcing the law requiring disclosures, and you have somebody you can go to if you have a question so you can get pre-clearance before you take a vote or an executive action, that’s certainly much better from the public’s perspective. And that’s what you’d want to see in a local ethics law.”

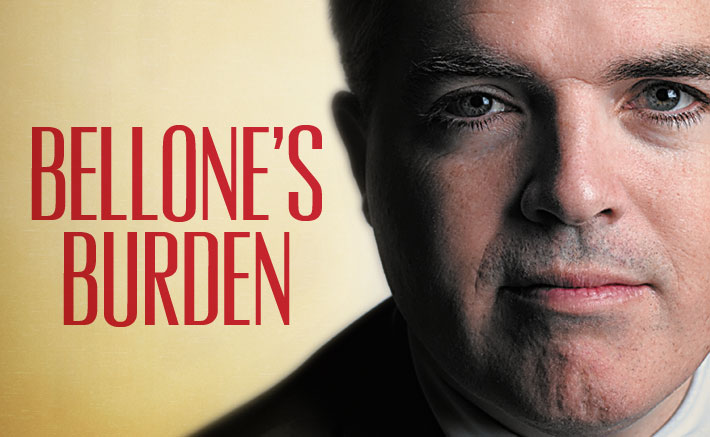

So far no smell of scandal and corruption has tainted the county executive race between Republican Angie Carpenter, the county treasurer, and Democrat Steve Bellone, Babylon Town Supervisor.

“Their ethics have not been called into question,” says Suffolk Republican Chairman John Jay LaValle. “Had Steve Levy run for re-election, it probably would have been an issue that we would have been discussing because I’m sure that Steve Bellone would have raised that issue against him.”

Bellone said that it was water under the bridge and that he applauded the new ethics legislation, which has bipartisan support.

“People need to know that public officials are doing the right thing to try and get our economy moving again and not doing things that benefit themselves,” Bellone says. “I think it’s more important than ever that people have confidence that the people they elect are working every day to help their lives and build a brighter economic future for our county!”

“Everyone should always be playing by the rules and I mean everyone,” says Carpenter. “Whether it’s me, or my opponent…or any other elected official, everyone should abide by the rules. The public has every right to expect nothing less.”