Once again WikiLeaks, an online organization dedicated to exposing state secrets, has grabbed the world’s attention by releasing a cache of confidential cables from U.S. embassies. This week the The New York Times began rolling out its coverage, with headlines like “Leaked Cables Offer a Raw Look Inside U.S. Diplomacy” and “From Arabs and Israelis, Sharp Distress Over a Nuclear Iran.” The tabloids offered their own take, such as the Daily News’ “Khadafy’s bodyguard of 1: sexy blond nurse.” Some argue that publishing this material was the right thing to do. But others, like Rep. Peter King (R-Seaford), the ranking Republican on the House Homeland Security Committee, claim that WikiLeaks founder, Julian Assange, an Australian, should be prosecuted. Has the public interest been served? Or have our journalistic standards been breached and our national security put at risk? Here to discuss are Jaci Clement, executive director of the Fair Media Council; Mark Grabowski, a journalism professor at Adelphi University and a lawyer; and Spencer Rumsey, senior editor at the Long Island Press.

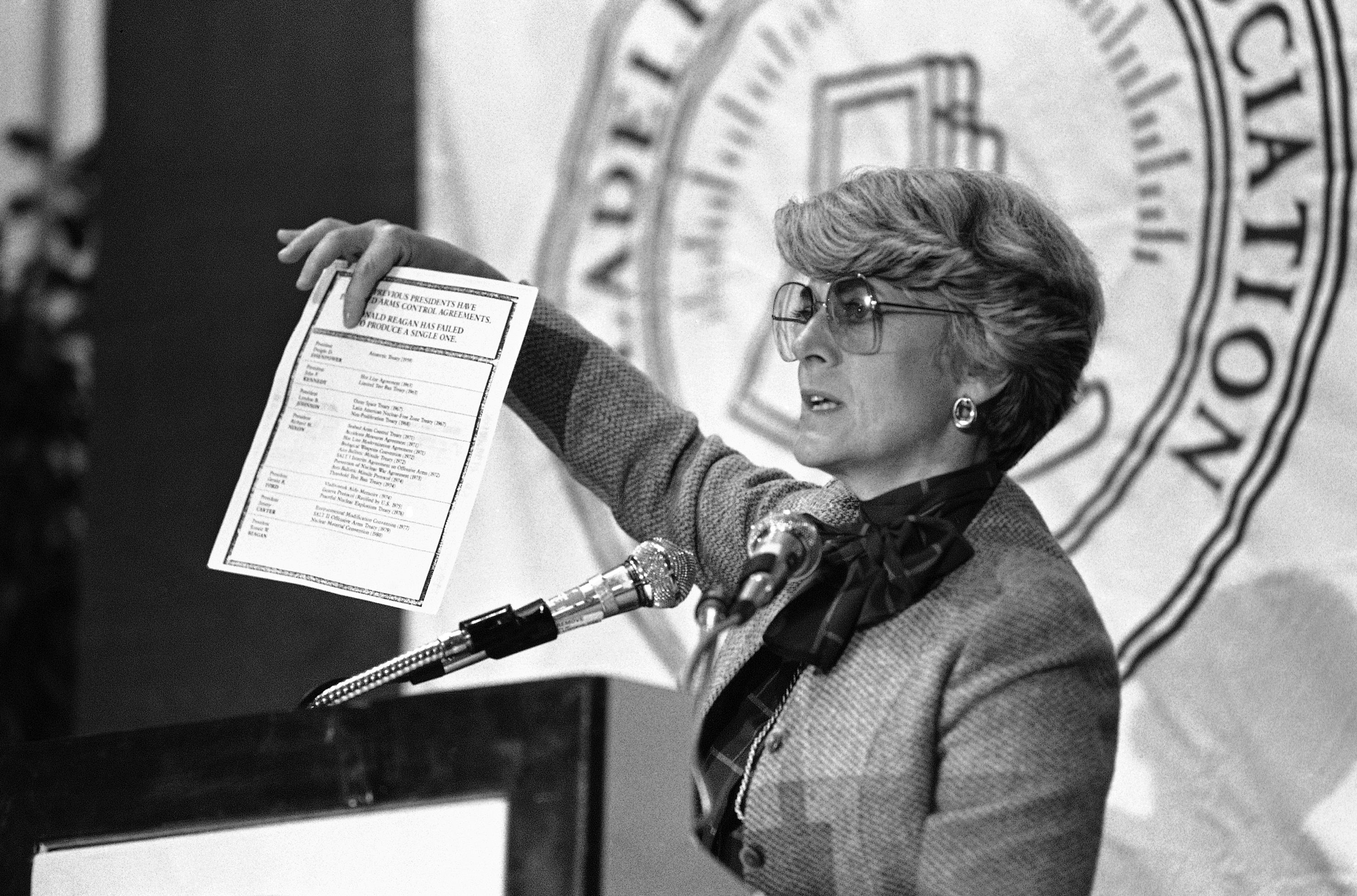

Once again WikiLeaks, an online organization dedicated to exposing state secrets, has grabbed the world’s attention by releasing a cache of confidential cables from U.S. embassies. This week the The New York Times began rolling out its coverage, with headlines like “Leaked Cables Offer a Raw Look Inside U.S. Diplomacy” and “From Arabs and Israelis, Sharp Distress Over a Nuclear Iran.” The tabloids offered their own take, such as the Daily News’ “Khadafy’s bodyguard of 1: sexy blond nurse.” Some argue that publishing this material was the right thing to do. But others, like Rep. Peter King (R-Seaford), the ranking Republican on the House Homeland Security Committee, claim that WikiLeaks founder, Julian Assange, an Australian, should be prosecuted. Has the public interest been served? Or have our journalistic standards been breached and our national security put at risk? Here to discuss are Jaci Clement, executive director of the Fair Media Council; Mark Grabowski, a journalism professor at Adelphi University and a lawyer; and Spencer Rumsey, senior editor at the Long Island Press.

Spencer: Graham Greene’s novel, The Quiet American, first published in the U.K. in 1955, mocked American idealism abroad. Next came Eugene Burdick and William Lederer’s best-seller, The Ugly American, which claimed that our own government deliberately keeps us in the dark about how our foreign policy is actually carried out. These cable revelations are part of that democratic tradition; but they’re not fictional, they’re factual. I don’t envy Secretary of State Hillary Clinton having to put out the fires, but I don’t think we’ll be hurt in the long run. The diplomats already know what’s up, why not all of us citizens?

Jaci: In times of war there has always been a different standard on what information may be made public. (Even weather reports were censored.) We are in a time of war. To release information that may compromise ending that war is the height of irresponsibility. While it may be amusing to read anecdotes on someone’s personal feelings toward world leaders, the time to do that is after they’ve passed on. These standards not only assure security but also protect us against unforeseen developments. Another issue is the American media’s history of myopic reporting. The only reason the U.S. press fails to cover international news and the viewpoints of other countries and their leaders is because the U.S. has enjoyed the status of a superpower. Reality check: We are no longer a singular superpower, and technology has shrunk the world.

Mark: “Seek truth and report it” is the first principle in the Society of Professional Journalists’ Code of Ethics. Journalists must “recognize a special obligation to ensure that … government records are open to inspection.” The Times is doing just that. The Code also states that journalists should “minimize harm.” But vague concerns about potential harm aren’t sufficient reason to stop publication. Of course, The Times must take care to ensure publishing information won’t directly or immediately harm anyone, such as an informant or soldiers. But there’s every indication they’re being judicious. I say, err on the side of openness.

Spencer: I wonder about prosecuting the WikiLeaks founder under the Espionage Act. Spies keep secrets, they don’t spill them unless they’re tortured. Julian Assange’s motivation is to open everything to public scrutiny. Should The Times be worried that it’s an accomplice to espionage?

Mark: The Times is merely a passive recipient of information. Once WikiLeaks put the documents out there (or announced they were going to), journalists couldn’t ignore it. Rep. King needs to stop shooting the messenger. This is the same guy who blamed the media for the Valerie Plame leak and said they should “be shot.” Of course, journalists shouldn’t be reckless with the information. It’s also tricky because there is an issue of patriotism. On the other hand, don’t we want our press to be objective? SPJ’s Ethics Code states: “Act Independently. Journalists should be free of obligation to any interest other than the public’s right to know.” If the Western media got their hands on secret documents from, say, North Korea, is there any doubt that they’d publish them?

Jaci: What’s at issue here is unforeseen ramifications on our future credibility. Who’s going to take the U.S. seriously or be willing to negotiate with us? The Times may well be carrying the bulk of the responsibility in this case. WikiLeaks may be able to claim it’s simply acting as a clearinghouse, whereas the Times’ has created its own content. Plus, the paper still publishes a print edition which, because communication law basically is place-specific, may ultimately be the most legally actionable aspect at play. This is huge, as it shines the light on how to hold anyone accountable for information posted online and, therefore, worldwide. Communication law is drastically out of date compared with technology.

Mark: I’m pretty sure that, legally, The Times is on solid footing. There’s a string of legal precedents going back to the Pentagon Papers case in 1971 that work in The Times’ favor and will make it difficult to criminally prosecute them. There’s a reason why the government is making serious legal threats against Assange but merely chiding the media. They know better than to mess with the press.