The Horvath floor is an unruly scrum of constant traffic and disparate creatures—e.g., a massive three-legged German shepherd called Patton, a manic Chihuahua called Bobo, an attention-hungry cat called Smudge, a couple of bunnies, not to mention Christopher and Sadie. Dodging all this activity is Skippity, a fish crow who cannot fly, who hops around the living room with the grace and dexterity of a wind-up toy. All oil-black feathers and wide open beak, Skippity came into the Horvaths’ lives two years ago: He was injured when he fell out of a nest at an early age; he suffered two broken wings and a broken leg. Today, he’s got permanent damage to both his wings (though his leg is fine) and as such, he’ll be living out the rest of his days with Bobby and Cathy. According to Cathy, Skippity talks—talks, like, in the clipped mimetic speech of birds, not like Mr. Ed—goes outside, goes in the bathtub with Sadie, plays a sock-fetch game with Bobo. He is a charming, delightful creature with an immediately winning personality: excitable, generous, playful, sweet, funny. You imagine he is unique among crows in this regard, though how would you know?

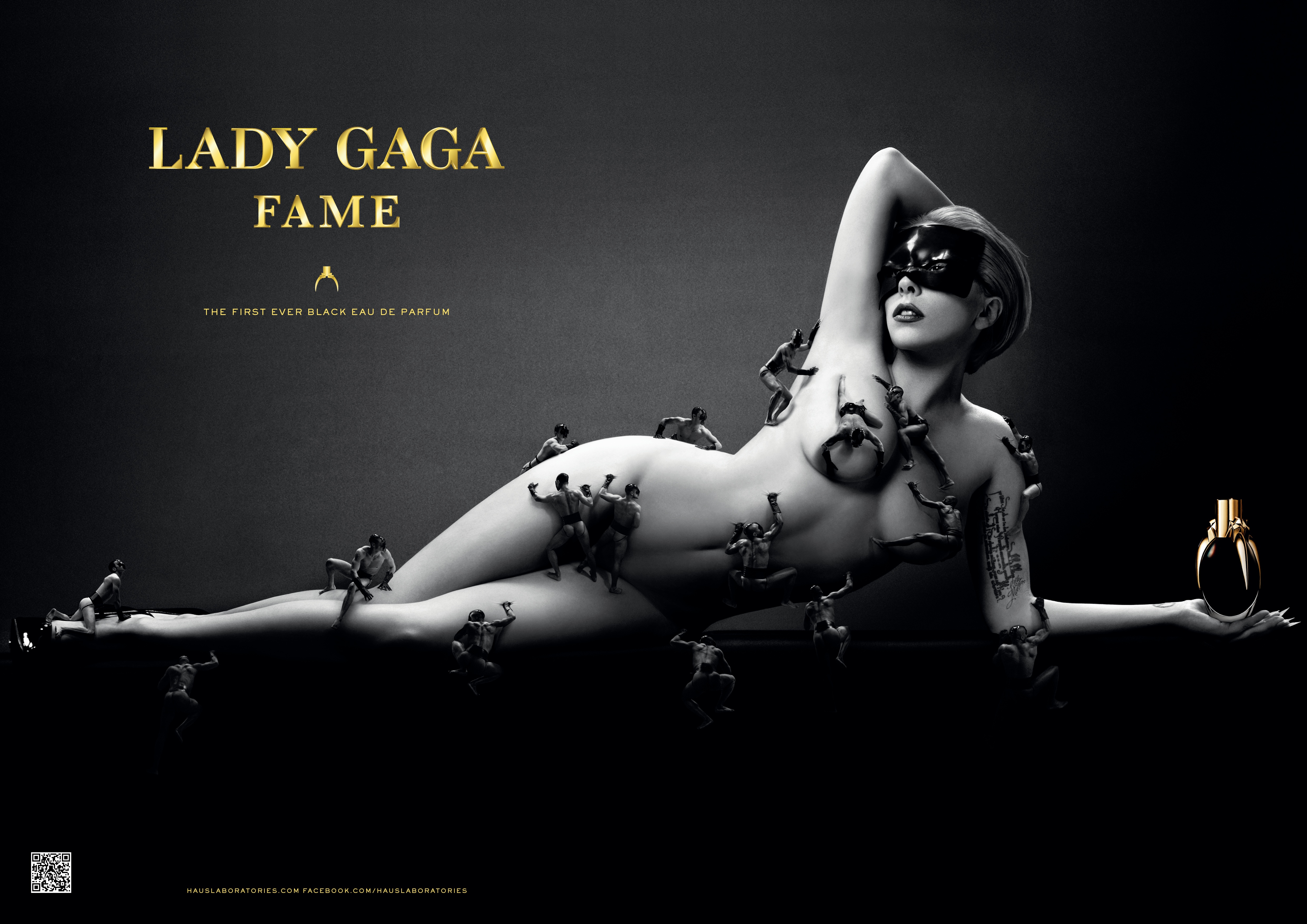

Sadie Horvath (seated) and Skippity the fish crow hang out on the Horvath living room floor. Skippity is sitting on Kathy Horvath’s sandal while Pete Richter chats about birds in the background.

Skippity is not overshadowed in this place—he’s a little bit of an attention hog, honestly—but he is one of many. Indeed, Cathy admits she would have to refer to her log book to determine the exact number of animals in her care at the moment. There are rabbits, dogs, a skunk, a bobcat, hawks, owls (numerous breeds of owls), falcons, kestrels (which are a type of falcon), chickens, turtles, baby squirrels, chipmunks, field mice, a bald eagle, night herons, monkey-tailed skinks, marmosets…

The marmosets came from the city, about seven months ago. They had been the property of a drug dealer whose operation had been busted by the cops. Along with some snakes and tarantulas—exotic pets de rigueur for any self-respecting drug dealer—the marmosets (a species of monkey that grows to about eight inches long) ended up in the hands of Animal Control. Animal Control called Bobby and Cathy, asking if they could take any of these animals. Bobby and Cathy said yes—because they do not say no—and they wound up with a pair of marmosets, a boy and a girl, and a handful of tarantulas.

The marmosets were thin, dirty, fearful—afraid of men, Cathy notes. But Cathy cleaned them and fed them and played with them, and today they are part of this zoo, in a cage near the air conditioner, a few feet from the couch, across from some kestrels. The marmosets swing to the front of the cage when visitors walk by, not greeting you so much as checking you out, like nosy neighbors. They have sharp teeth, for ripping bark off trees; they have small fingers, which wrap around the bars of the cage, and gentle, sad, searching eyes.

Calls like that one—the one that brought the marmosets to the Horvaths—come from the police, from animal control, from different shelters, from animal hospitals, from other rehab facilities, from people everywhere. Especially now. This is fledgling season, and young birds are being pushed out of nests on to hard ground, breaking wings and legs. The other day, for example, on his way back to Massapequa from releasing into the wild a pair of baby hawks, Bobby called home to check the voicemail, and six messages had come in over the course of a few hours: a peregrine falcon in Manhattan; a goose in Syosset; ducklings in a drain hole in Massapequa; kestrels in Brooklyn.

Most people want to help animals. Most people have no idea.

Bobby and Cathy have been licensed by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) as well as U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service since 1998; they have taken in more than 200 animals since January 2010 alone. They are not a center, not a government body, not a private petting zoo. They are volunteers—saints, perhaps—a family. They do educational programs for schools, Boy Scouts, libraries, the Audubon Society. They call themselves an organization, but it’s a loose collective at best: There’s an orthopedic surgeon whom they trust, Dr. Ellen Leonhardt, in East Norwich; there’s the guy at the fish market who sometimes cuts deals on fish for Bobby, to help feed the birds; there are a few other local rehabilitators who take on a small number of animals at a time, but nothing on the scale of Bobby and Cathy. (For his part, Bobby knows of no one in the country, short of rescue centers, doing such work.)

“As far as rehabilitating or rescuing animals,” says Cathy, “it’s me and Bobby. We’re the only crazy people who travel from Manhattan to Montauk, and everywhere in between, picking things up. We pretty much do this on our own.”

This is not an inexpensive proposition, and most of the costs come out of Bobby and Cathy’s paychecks. Cathy works as a vet technician; Bobby is a New York City firefighter. They do not charge for their services (legally speaking, they cannot charge for their services). They receive no state or federal funding. Their organization—Wildlife In Need Of Rescue & Rehabilitation, or WINORR, founded in 2002—is a not-for-profit, but most of the donations are sporadic and minimal. Maybe $10 here, $20 there.

“Yesterday a guy came and he gave me $25, which is a huge help, but that’s what we get,” says Cathy. “We do it out of our own pocket.”

Bobby says they are eligible for grants, but they have neither the time nor the inclination to fill out the extensive paperwork necessary to receive such funding. “We’re not grant writers,” he says. “We do the grunt work: climbing ladders and cleaning cages and rescuing birds.” He hopes one day they’ll find the time to address those lengthy administrative details, hopes the money will someday make its way to his family, his organization, the animals in his care. But that takes work, a lot of work—and as it is, Bobby and Cathy take in more than 500 animals a year; they are already working. “We struggle to get everything fed and cleaned every day,” he says.

And while both Bobby and Cathy refer to this, separately, as a “calling,” they both also admit it can be taxing, stressful.

“This is our life,” says Bobby. “We can’t travel, we can’t vacation. At some point, now that I’m raising a 3-year-old daughter, I’m going to want to do all that.”

Bobby plans to retire in the next three years, at which point he hopes to find a way to do animal rescue full time. He admits that others may think he’s out of his mind—his own family, he says, doesn’t understand his passion. His neighbors occasionally object to the smell, the noise: The bobcat isn’t too concerned whether there’s a pool party going on next door; baby crows are not known for being silent, regardless of the unwritten (or written) laws of suburbia. It’s up to Bobby and Cathy to be good neighbors, and that demands additional hard work. Furthermore, they have put significant demands on their friends, their families, their relations. They miss engagements, come late. They spent the last three New Years Eves in Manhattan…picking up injured hawks.

“We make great sacrifices,” says Bobby. “I’ve missed holiday parties, been late to birthday parties, been late to a variety of social engagements because as we’re getting ready to walk out the door, someone will call with an emergency, and we look at each other and say, ‘Look, we’re it. There’s no one else. It’s Saturday night at 8 o’clock at night. There’s no one else to call.’”

They are already overextending themselves, says Bobby. Still, he says, “The majority of times, we do say yes.” (Continued…)